Volume Ten – 1789 – 1837

The Last of the Hanoverians

KING GEORGE’S MADNESS

THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR

THE CONDUCT OF PRINCESS CAROLINE

SLAVERY THROUGH HISTORY

THE ASSASSINATION OF SPENCER PERCEVAL

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

JANE AUSTEN

FREE TRADE AND PROSPERITY

WILLIAM THE FOURTH’S CORONATION

KING GEORGE’S MADNESS

When the old King died (sadly, on the loo),

It was out with the old, in with the new.

The prospect of a youthful, virile King

Was a breath of fresh air, a touch of spring.

His manner was “graceful and obliging” –

This from, of all people, Horace Walpole.

Tolerably good-looking, on the whole,

His reign was something of a watershed.

For George was the first monarch born and bred

In England since the time of good Queen Anne.

Despite the late Queen’s nickname, ‘Brandy Nan’,

Her fragile popularity, bless her,

Eclipsed that of her German successor,

George the First, and his son, George the Second,

Both brought up in Hanover, and reckoned

Far too ‘European’ for their own good.

Now here was a better George who (touch wood)

Promised otherwise. For he spoke plainly:

“Born and educated in this country,

“I glory in the name of Britain.” See?

This explains his early popularity.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR

The Battle of Trafalgar was a rout.

The final outcome was never in doubt.

Disposed in a semi-circular arc,

The combined French fleet failed to make its mark.

Nelson breached their serried ranks right away

And in no time at all he won the day.

Fighting at close quarters, as was his way

(Remember the Nile?), ship-to-ship, pell-mell,

He gave the French, poor devils, merry hell.

Some 6,000 men the enemy lost,

Killed or wounded, a most terrible cost.

Out of their total fleet of thirty-four,

Sixteen ships were ‘disabled’ (maybe more),

The remainder sunk or captured. This score,

A stunning tally, decided the war,

In terms of the sea, for the next ten years.

Trafalgar gave rise to the most bitter of tears –

The greatest naval triumph in our history.

Nelson, on the quarter deck of the Victory,

Was shot by a sniper. He was brought final news

Of the battle by Hardy. Whatever one’s views

(“Kiss me, Hardy” and all that), the piteous loss

Was felt by his men. Sailors rarely give a toss

For their admirals or captains. Nelson inspired

Respect, admiration and love. He expired

In Hardy’s arms, this most singular of heroes.

Now, as almost every schoolboy knows,

Nelson had sent a signal to his fleet

Designed to guarantee a French defeat:

“England expects” (this is a rare beauty)

“That every man will do his duty.”

I suggest that the compelling irony

Is that this message was unnecessary.

There was not a single shirker on board.

Their love for their boss was fixed and assured.

October the 21st was the date

That Horatio Nelson met his fate.

The King was cool. He was barely upset.

He spoke in terms of the mildest regret.

For George, a moral man, was well aware

Of Viscount Nelson’s scandalous affair

With Emma, Lady Hamilton. “He died

“The death he wished.” That’s some epitaph, snide,

Bald and callous. He might at least have tried.

Pitt, on the other hand, was mortified.

In Downing Street, a mere six weeks before,

He’d held with Nelson a council of war.

Horatio had promised victory

And later proudly told his family

How Pitt, in person, had escorted him

To his carriage. The prospects were grim,

But each held the other in high regard.

Within the space of five months (this was hard)

Both lay dead – Nelson at forty-seven,

Pitt at forty-six. We should thank Heaven

For their dedication to duty

And public service. The King was snooty

(As we’ve seen) at news of Nelson’s demise,

But Pitt knew his worth, which was no surprise.

The tidings came at night and broke his sleep,

Causing the mighty Pitt to sit and weep.

Two days after the report reached London –

Of Nelson lost and of Trafalgar won –

Pitt delivered a speech at the Guildhall.

The crowd pulled his carriage. Walking tall,

Pitt nonetheless claimed no credit at all.

The Lord Mayor of London was a fan:

Europe had been saved and Pitt was the man.

The First Lord’s reply was short and modest.

Europe was not to be saved, he confessed,

“By any single man”. England, at best,

Had saved herself by her own energies.

She would “as I trust” bring France to her knees

And “by her example” save Europe. These,

Pitt’s most telling words, are fit testimony

To his high honour and sense of destiny.

Back to top / Buy the book

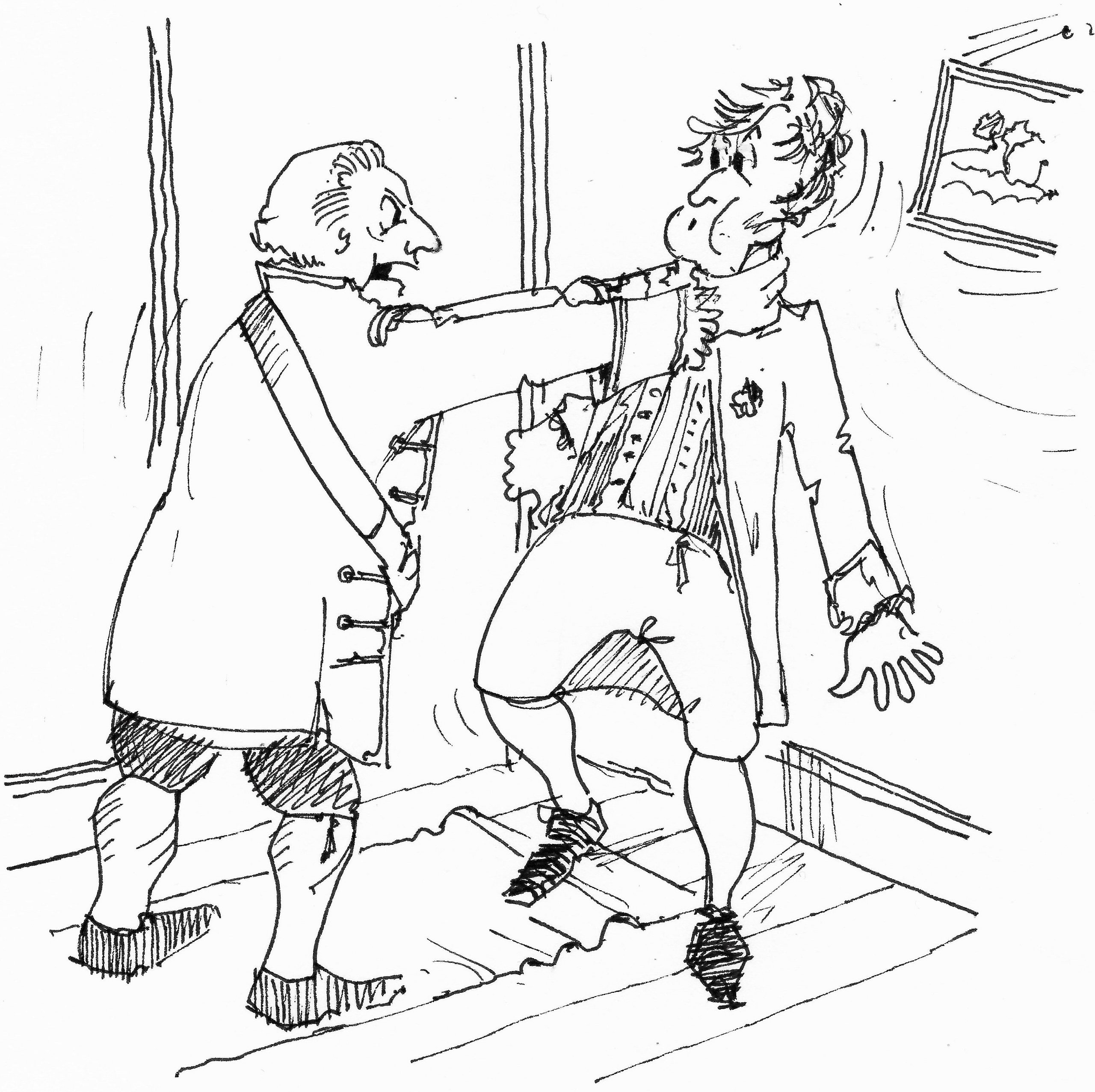

THE CONDUCT OF PRINCESS CAROLINE

A ‘delicate investigation’,

So-called, confirmed the reputation

Of the Princess as a woman of “rash

“And imprudent conduct”, bold and slapdash.

Yet her character was deemed “kind-hearted

“And generous”. What had the King started?

For when George had given his permission

For an investigative Commission –

With some reluctance, it has to be said –

He must surely have taken it as read

That the end result would be conclusive.

Not so. Some witnesses were abusive:

Many there were prepared to dish the dirt.

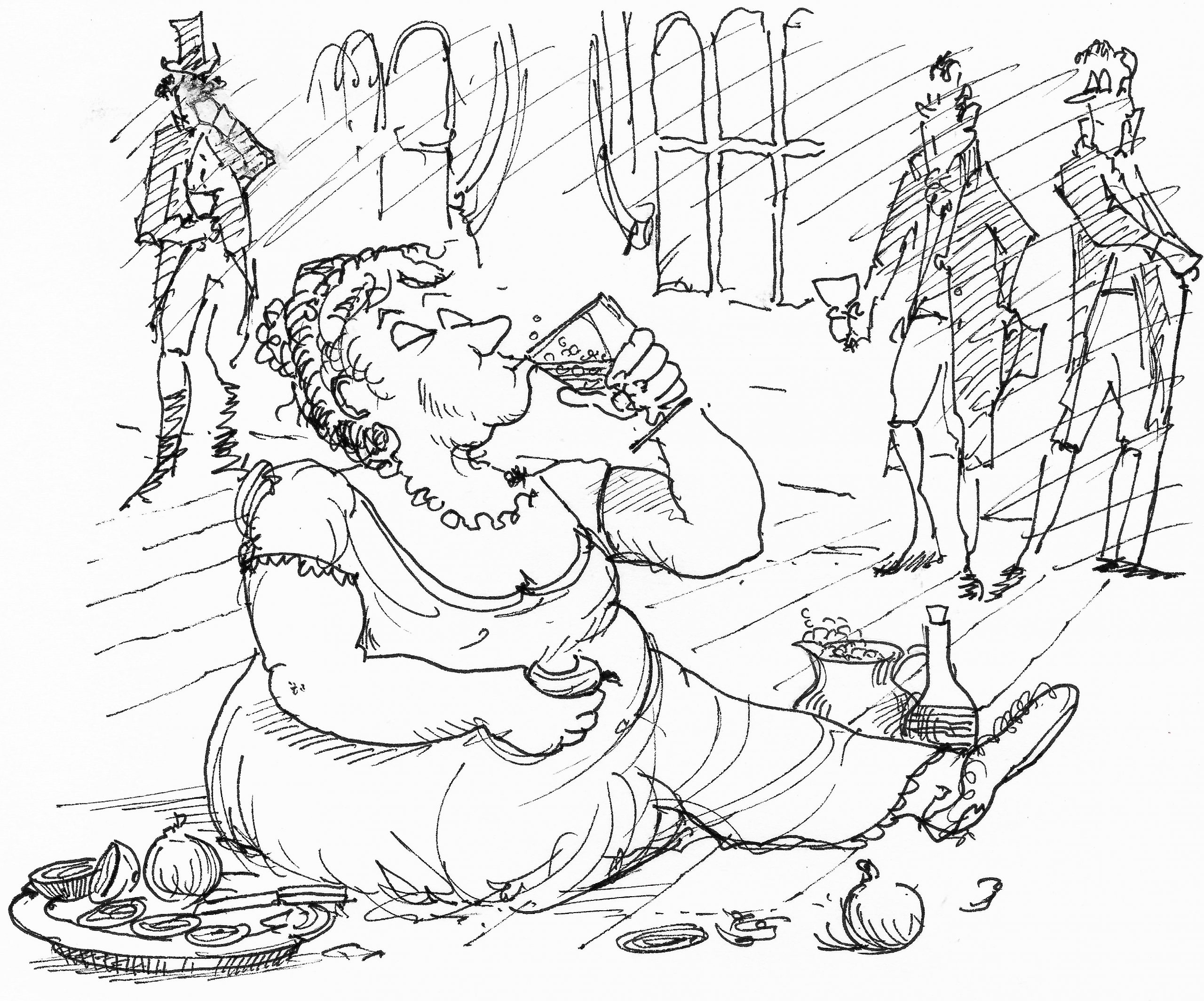

Caroline confessed to being a flirt.

She relished the company of young men,

Entertaining them in her chamber. Then

(Horror of horrors) she’d squat on the floor,

Quaffing beer and eating onions galore!

Others dismissed these stories as nonsense:

Caroline, a model of innocence,

Sobriety and tact. Their evidence

Contradicted more hostile witnesses.

This was the most moral of Princesses.

The Commission of Enquiry found,

In its wisdom, not one credible ground

For the charge that she’d borne a secret child.

Nonetheless, her conduct had been rash, wild

And ill-advised. She’s alleged to have said

She could take a fellow into her bed

“Whenever I like”. “Wholesome,” she called it.

Such a woman was palpably unfit

To belong to the royal family.

No firm proof was found of adultery,

But the “levity and profligacy”

Of which Caroline was indeed guilty

Disqualified her, as far as George could see,

From all but “outward marks of civility”.

The Commissioners, to a high degree,

Had demonstrated too much leniency

Towards the vulgar, unprincipled Princess.

So argued the Prince of Wales, in some distress.

There had been more than enough in the hearing,

By way of proof, to petition the King

To dissolve his marriage, with the consent,

Of course, and sanction of Parliament.

You might feel greater sympathy with the Prince

Were it not for the knowledge that he, long since,

Had committed adultery, worst of crimes,

Not dozens, not hundreds, but thousands of times.

Back to top / Buy the book

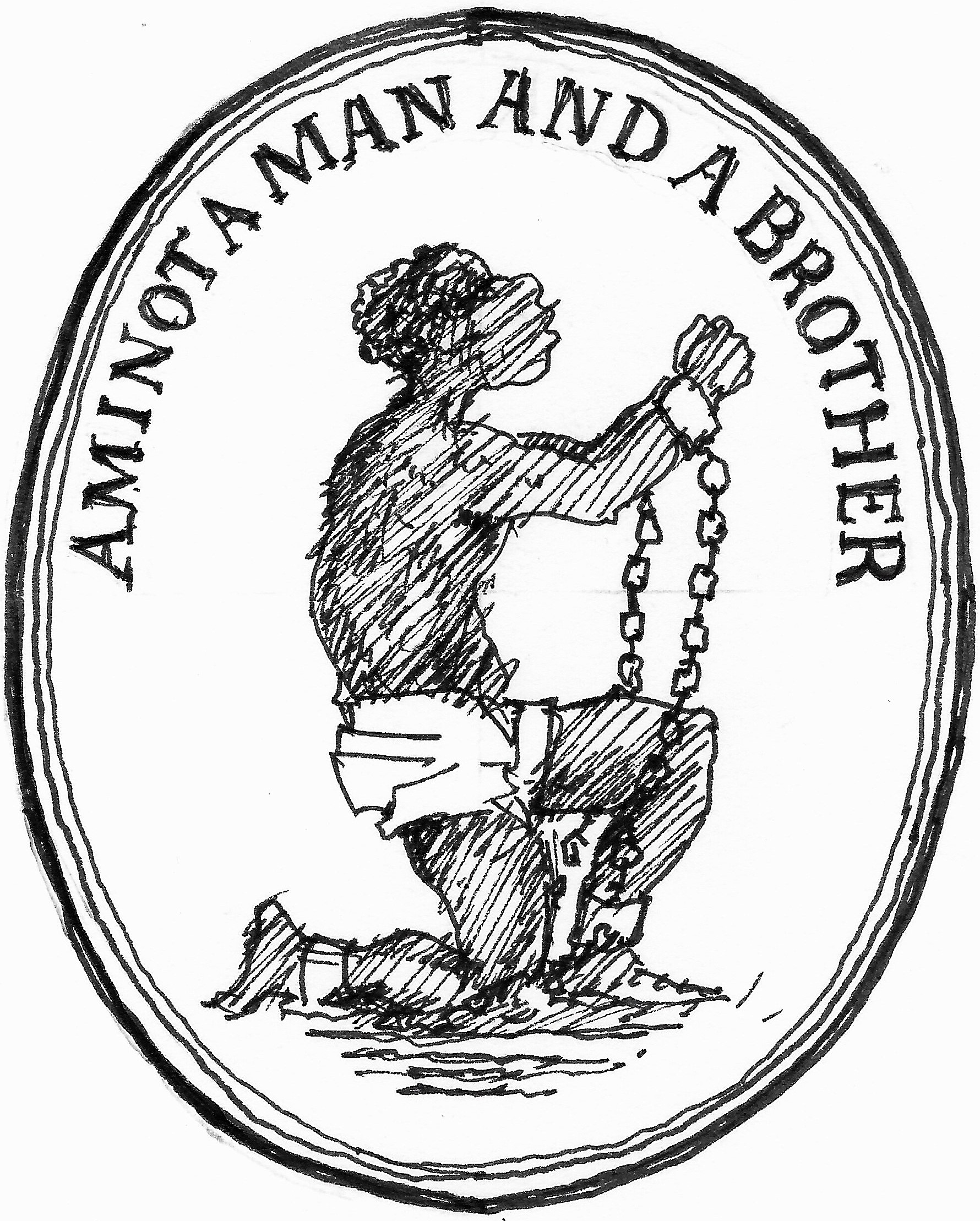

SLAVERY THROUGH HISTORY

Slavery was nothing new, sad to say.

Ancient Egyptians, in their heyday,

Traded in slaves. Persia’s King Xerxes

Scoured Ethiopia, if you please,

For the pick of the crop. Rome, in its prime,

Boasted some two million slaves. A crime?

Not in their book. Black slaves from Africa,

Celts from the fringes of Hibernia,

And Saxons to boot – all par for the course.

With the ease that you could purchase a horse,

You’d pick up a slave, examine his teeth,

Poke him and prod him. It was past belief.

In the Middle Ages, ‘Christian’ Spain

Enslaved the native Muslims. And again,

Centuries later, I’m sorry to say

(I’m talking here of Wilberforce’s day),

Many of those who went in for the kill,

Opposed to his Abolition Bill,

Were Christians to the tips of their toes.

Plus ça change (it’s true), plus c’est la même chose.

In Spain Christians got their come-uppance,

I’m pleased to say (I couldn’t care tuppence),

When the country was conquered by the Moors.

To a round, no doubt, of Muslim applause,

Christians in their thousands were enslaved,

A sharp reminder of how they’d behaved.

A trans-Saharan slave network, alas,

Thrived as black slaves were transported, en masse,

From West Africa to the fertile lands

Of Araby, employed, one understands,

As soldiers and palace lackeys, or sold

On the burgeoning export market. Gold,

Ivory and men… Why discriminate?

All offered for sale at the going rate.

The first half of the sixteenth century

Saw slaves, captured on the coast of Guinea,

Shipped as traffic across the Atlantic.

Stripped of all human dignity, frantic

And petrified, this African cargo –

The slaves, God help them, could hardly say no –

Were sold as labour in the New World. Gold

Was the fabled treasure, in need, we’re told,

Of uncomplaining miners. Sugar cane

Stoked an increasing demand. To explain

Is rarely to excuse. This wicked trade,

From which gargantuan profits were made,

Was pioneered by the Portuguese.

They sent cheap and shoddy goods overseas

To Africa. These they would exchange for slaves.

Many were destined for watery graves

As they perished, poor souls, on the high seas –

The ‘middle passage’ to the West Indies

And the Americas. Those who survived

Were put to work, as soon as they arrived,

Sold, in bondage, to the highest bidder:

Mere objects, with no pride to consider,

No better than animals. In one case

In 1783 (a disgrace)

England’s Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, swore

That a slave had no higher right, in law,

Than a horse. A ship’s captain might, therefore,

Throw him overboard without penalty,

Dead or alive. Mark that: in ’83.

No advance since the sixteenth century.

The next ‘leg’ of the trading ‘triangle’,

The third lap of this ghastly fandangle,

Was shipment back to the mother country

Of every conceivable luxury:

Pearls, spices, skins, sugar – at vast profit,

But dreadful human cost. Fair trade? Come off it.

It won’t come as any surprise to you

That as early as 1562

The greedy Brits muscled in on the act.

Good Queen Elizabeth (I’d best show tact)

Was apparently content to approve

A scheme by one John Hawkins to remove

Three hundred or more ‘negroes’ from Guinea

For sale in Hispaniola. To me,

This smacks of rank royal hypocrisy,

For the Queen pledged her support in the hope

That the poor slaves (little more than soft soap)

Would not be transported against their will –

And she an intelligent woman! Still,

The voyage went ahead (are we surprised?)

And Hawkins is said to have realised

A rich profit. England never looked back.

She led the world in this cruel attack

On human dignity. The British trade

Boomed (I know you’ll be suitably dismayed)

With the development of colonies

In the Americas. The Portuguese

Were eclipsed. In the 1740’s

Over 200,000 slaves were shipped

To the West Indies by the British, whipped,

Beaten, starved, parched and stricken with disease.

Sad to say, by the 1780’s,

When Wilberforce embarked on his campaign,

The number had nearly doubled again:

Three-quarters of a million worldwide,

Almost half in British ships. You decide.

How was this possible to justify?

The wealth of Britain was hard to deny.

Eighty-five per cent of English textiles

Were exported to Africa. Lifestyles,

For all classes, improved accordingly.

The greater part of British industry

Was dependent, alas, on slavery,

The very foundation of our commerce.

The prospects for reform could not have been worse.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE ASSASSINATION OF SPENCER PERCEVAL

This able Prime Minister’s three-year stint,

In difficult times, gave more than a hint

Of future promise. Finance for the war

Was well managed. Perceval set great store

On detail. Wellington gained ground in Spain,

Napoleon’s fortunes were on the wane,

But the war was a long-drawn-out affair.

Perceval never gave way to despair,

Doggedly piloting the ship of state

Through choppy waters. Spencer’s tragic fate,

Sad to say, was assassination.

The sorrow and shock to the nation

Were not to be underestimated.

True, some idle hot-heads celebrated,

Sniffing revolution in the air –

Blind to Perceval’s talents, I declare.

Every Prime Minister’s worst nightmare

Had come to pass. For Perceval was shot

In the Commons’ lobby. There was no plot.

This was the work of one crazed assassin –

No revolutionary Jacobin,

But a man with a grudge, John Bellingham,

Who blamed Perceval (according to some)

For losses that he had suffered in trade

In Russia. Bellingham, unafraid,

Had approached his victim, produced a gun,

Unnoticed at the time by anyone,

And fired at close range into his chest.

Then he calmly sat to await arrest.

“Oh, I am murdered… ” poor Perceval cried.

Beyond all help, within minutes he died.

Spencer Perceval was mourned far and wide.

The country, to a man, was mortified.

At the Old Bailey Bellingham was tried

And, after a hearing lasting one day,

Was found guilty. On the 19th of May,

Just eight days after his dastardly crime,

He went to his death – in double-quick time.

With little pomp or ceremony

Perceval was buried privately.

Devoted to his growing family,

He would relax by slipping quietly

Into the hubbub of the nursery.

There he would play for hours, happily,

His death a great domestic tragedy.

Back to top / Buy the book

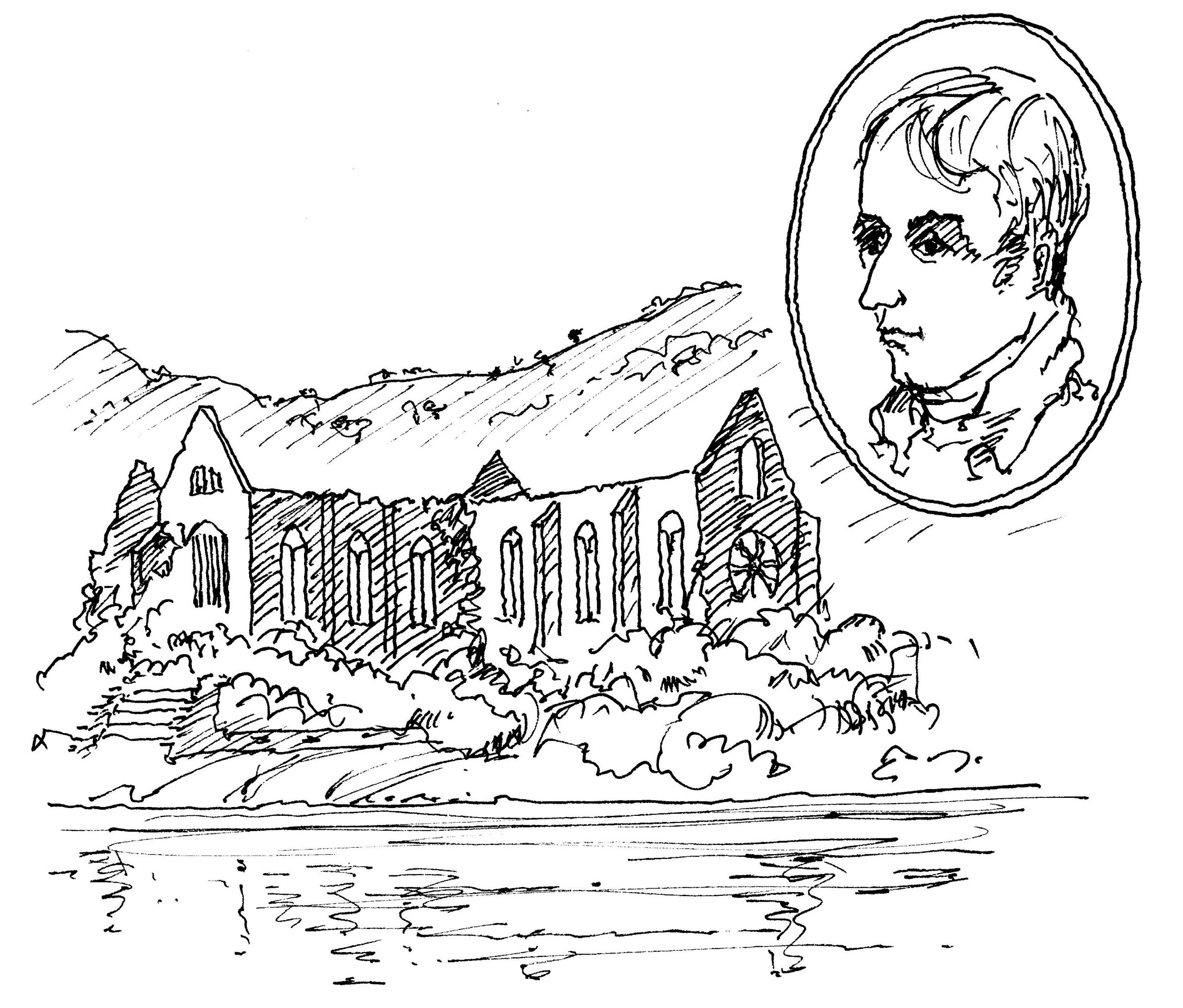

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

The true poet of Nature was Wordsworth.

From Cockermouth, a Cumbrian by birth,

William would commune “with all I saw” –

A lapwing, a solitary jackdaw,

The music of a wren or, in the trees,

The stirring breeze. Sounds and sights such as these

Were the lifeblood of Wordsworth’s poetry –

Artless, unaffected imagery.

He sought a natural simplicity

In language, as in subject matter –

No overblown, poetic ‘chatter’,

But a plainness bred of experience

And the strange mystery of innocence.

No contradiction there. Incidents

Born in childhood, stored in the memory,

Were transfigured by his capacity

For feelings of profound intensity

Into living verse. Sensitivity,

Observance and a choice facility

To harness emotion to his will

Render Wordsworth’s lines accessible still.

“Earth has not anything to show more fair…”

Ironic! Simple, yet so rich and rare.

His nature poems are beyond compare.

“How oft, in spirit, have I turn’d to thee” –

This of the “sylvan Wye”. Tintern Abbey

Was dashed off, in a kind of rhapsody,

After a visit to the Wye valley.

The “still, sad music of humanity”

Moves the poet, “not as in the hour

“Of thoughtless youth”, but with “ample power

“To chasten and subdue”. A “sense sublime”

He feels, born of experience and time –

“A motion and a spirit that impels

“All thinking things”. The meadows, woods and fells

And “all that we behold of this green earth”

Inspire the contemplative Wordsworth

With “the joy of elevated thoughts”. Well,

No better testimony, truth to tell,

Could I conjure of Wordsworth’s sylvan wings –

His quest to see “into the life of things”.

He tells of his childhood in The Prelude,

His early life, the joy of solitude.

These lines on the French Revolution

He wrote with youthful resolution:

“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” –

His early passion didn’t long survive –

“But to be young was very Heaven!” Please,

Steep yourself in such sentiments as these.

Resolution and Independence,

For sheer compassion and plain good sense,

Is a gem. But my favourite of all

Is The Solitary Reaper. Walk tall,

William Wordsworth! We all read aloud,

At school, I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud –

The first introduction, for many,

To English verse and as good as any.

Back to top / Buy the book

JANE AUSTEN

The Prince Regent was a great devotee

Of the novels of Jane Austen. She was free,

He hinted, to dedicate one to him!

This fancy was far from an idle whim.

He adored her books and kept, if you please,

All six in each of his residencies.

George, a man of sophistication,

Was sent, prior to publication –

Complete with its own dedication

To “His Royal Highness the Prince Regent” –

Jane’s fourth novel, Emma. She was content

To accept the patronage, and why not?

George, at his worst a calamitous clot,

Libidinous ass and dissolute sot,

Nonetheless as a collector, patron

And friend to the arts was second to none.

The superb Miss Austen, all said and done,

Was the finest novelist of her age,

Arguably of all time. Take the stage,

The Dashwoods, Elinor and Marianne.

This first novel, far from an also-ran,

Is magic: Sense and Sensibility –

Moving, yet high-spirited and witty.

The author’s “miniature delicacy” –

Charlotte Brontë’s illuminating phrase –

Is already apparent. Beyond praise

Is Jane’s second book, Pride and Prejudice,

Though she herself wrote of the style (mark this)

“It lacks shade”. Miss Elizabeth Bennet

(Prejudiced, true) rises, to her credit,

To the challenge of Mr. Darcy, proud,

Handsome and arrogant. Her mother, loud,

Embarrassing and shallow; her sister,

Lydia (how could Wickham resist her?);

The appalling Mr. Collins, buffoon

And snob… The book is finished all too soon.

For observation and irony,

On her precious “bit of ivory”

(David Cecil’s words) Jane Austen dug deep.

There are times when you could willingly weep:

Miss Bates at the Box Hill picnic (Emma)

Is a choice scene you’ll ever remember,

Toe-curlingly cruel, yet comic still;

Sweet Anne Eliot, pressed against her will

To dash the hopes of Frederick Wentworth;

Her haughty father, baronet by birth,

Obsessed with class, society and rank;

Anne’s hopes restored, with Frederick to thank…

Persuasion, this fine, autumnal book,

This little gem, is worth a second look.

Northanger Abbey is wonderful fun,

A ‘spoof’ on Mrs. Radcliffe. Number One,

However, for many is Mansfield Park,

A more complex book. The contrast is stark,

Though it’s not always noted, between this

And the sunnier Pride and Prejudice:

The Crawfords, their amateur theatrics,

Simple Fanny Price – an intriguing mix;

While lurking in the wings of Mansfield Park

Is the sordid reality, raw, dark

And shameful, of the hideous slave trade.

Consider afresh the vast fortunes made

By the British. Sir Thomas, if you please,

Blithely sallies forth to the West Indies

To settle his estates. In his absence

There’s a huge helping of idle nonsense

Caused by love affairs, rehearsals of plays,

Petty jealousies and the awkward ways

Of youth. Wealth and privilege, in those days,

Were subsidised by slavery. A hint,

A mere glimpse, does Jane give, taking the glint,

For a brief moment, off the ivory –

A quick peep at the dread reality

Behind this cosseted society.

I’ve not the faintest notion, truly,

Whether Jane Austen was pained unduly

By thoughts of slavery. She’d have known,

One imagines, how cotton was grown,

How sugar was produced, the cruelties,

Atrocities and gross indignities

Suffered by workers in the West Indies.

Or was this one of those societies

Where ignorance was bliss? I don’t buy it.

Folk knew. I challenge you to deny it.

Back to top / Buy the book

FREE TRADE AND PROSPERITY

Lord Liverpool stood for freedom of trade.

Hesitant steps had already been made

Along this road. The movement gathered pace

From 1823. It’s no disgrace,

I’m pleased to report, that prosperity

Reigned. “Never was a country so happy,”

Wrote Princess Lieven in a long letter

To one of her best friends in Vienna.

Closer to home Lord Liverpool, no less,

Was writing to George Canning to confess

That “Britain was never in such a state

“Of internal welfare and content”. Wait!

I have little doubt that a family

On a low income was far from happy.

Scandalous poverty still stalked the land.

Liverpool was talking, you understand,

In broad economic terms. An upswing

In activity (hardly surprising,

Given years of tight fiscal management)

Was widely welcomed by Parliament,

Most particularly the announcement

That taxes were to be slashed. At a stroke,

Chancellor Robinson (popular bloke)

Axed one-and-three-quarter million pounds

Of levies. There were more than ample grounds

For optimism. The following year,

In a step that raised a resounding cheer

From economic liberals, a move

Was made at last to reduce or remove

A whole swathe of duties: on rum, on coal,

On wool and even on silk. On a roll,

Liverpool was edging towards free trade.

The first foundations were being laid

For the economic prosperity

Of the mid- to late-nineteenth century –

The early tentative moves, anyhow.

Step forward Lord Liverpool. Take a bow.

The 1825 budget maintained

This momentum. Much advantage was gained

By reducing duties on rum, coffee,

Wine, cider and hemp. What a novelty!

Here was an integrated policy

Designed to guarantee prosperity:

Fairer taxation; encouragement

Of the export trade through less ‘government’

And fewer prohibitive duties; and –

In a spirit that all could understand –

A shot in the arm for home industry,

The domestic market. This was the key:

A rounded economic strategy.

There came the odd hiccup. That’s politics.

In the late spring of 1826

A shortage of corn and (a lethal mix)

A surprise slump in manufacturing

Led to a wave of widespread rioting

And (up in Lancashire) machine-breaking.

The price of grain sky-rocketed of course.

Farmers and landowners yelled themselves hoarse

In a vain attempt to raise the ‘threshold’

Of the Corn Laws. Lord Liverpool, we’re told,

Was not to be moved. His response was cold.

There could be little justification

In forcing a starving population

To pay above the market price for food.

The protective measures in place were crude

And regressive. They’d not be extended.

Agriculturalists were offended

(Surprise, surprise) by the modest release

Of new supplies of corn and the decrease,

As a result, in the price to the poor.

That is what strong Prime Ministers are for.

Back to top / Buy the book

WILLIAM THE FOURTH’S CORONATION

A diversion. A brief holiday.

September the 8th, I’m happy to say,

Was William’s Coronation Day.

To the King himself this was no big deal.

Pomp and circumstance held little appeal

For this most down-to-earth of men. His view

Was that the whole vulgar hullabaloo

Could with best advantage be dispensed with.

All coronations were expensive.

His brother’s had cost (the figure astounds)

Some two hundred and fifty thousand pounds –

A glaring case of daylight robbery,

A show of privilege and snobbery.

The King was wedded to economy,

But the press (and the average Tory)

Insisted, for the sake of history,

On the full works. When it came to the crunch,

The guests, we’re told, were to bring their own lunch,

While the total cost of the whole affair

Was forty-three thousand. Will was aware,

Well aware, of the country’s sombre mood.

Squandering excessive money on food

(Though there was dinner) was not to his taste.

An orchestra? A most terrible waste.

A simple fiddler was just the thing –

A natural air on a single string.

The ushers in the Abbey (volunteers)

All paid for their own outfits. It appears,

Furthermore, that in the case of his crown –

George the Fourth would never have lived this down –

The King refused to have it remodelled,

Just padded. The Queen was mollycoddled.

Adelaide, to her joy, was permitted

A spanking new crown. At least it fitted.

Back to top / Buy the book