|

HENRY THE SEVENTH (1485 – 1509) The new King Henry the Seventh had brains. The King was a man of some piety, Pictures suggest a frail man wracked with care, On April the 21st, 1509, |

|

HENRY THE EIGHTH (1509 – 1547) Prince Henry succeeded. With Arthur dead, England was stuck with his brother instead. King Henry the Eighth, aged barely eighteen, Was set, within weeks, to marry his Queen. Catherine, Arthur’s widow, had waited |

|

But for now there was wild jubilation: A royal wedding, a coronation, A handsome young King in the prime of life, Virile and strong, with a fine Spanish wife. Henry was all that his father was not. Henry thought rather a lot of himself. In his own eyes Henry could do no wrong – |

|

HENRY THE EIGHTH’S LAST FIVE WIVES Anne Boleyn Anne Boleyn: an unhappy marriage. The sad young Queen suffered miscarriage After miscarriage. So, still no son. The King only married, all said and done, To father an heir – as simple as that. Princess Elizabeth, snivelling brat, Wasn’t a boy. She wouldn’t do at all. So Henry contrived her poor mother’s fall. In 1536, early in May, |

|

Jane Seymour The lucky lady was one Jane Seymour. She’d caught the King’s lustful eye months before. She must bear him a son, and she knew it. Dying in childbirth, she nearly blew it – But the infant survived. It was… a boy! An heir at last! The people danced for joy! Tragic for Henry to lose his new wife, But baby Edward, the light of his life, Furnished the King with justification For all his past errors. Jubilation Replaced despair as the English nation, Sure at last of the continuation Of the House of Tudor, simply went wild. The wife of the King had borne a male child! |

|

Anne of Cleves The hunt was soon on for a replacement. Cromwell, never one for self-effacement, Set about this commission with a will. Thomas, though, sadly showed limited skill In the match-making department. His fear – Deep-seated and increasing year by year – Was that amity between France and Spain Would isolate England. Time and again He warned the King of imminent danger. Self-appointed ‘marriage-arranger’, He sought a political alliance With the Duke of Cleves – not in defiance, Exactly, of the King, but he worked hard To win Henry over. Cromwell’s trump card Was that Cleves had a sister (another Anne). Cromwell was canny and cooked up a plan. Their short marriage was celebrated, |

|

Katherine Howard Within sixteen days of the royal divorce, This loyal servant of the Crown died. Of course, The King remarried, and on the very day That Thomas met his Maker. I have to say That for bare-faced cheek that takes the biscuit. And Wife Number Five? Who’d want to risk it? – The Duke of Norfolk’s niece, one Katherine, Cousin (can you believe?) to Anne Boleyn. Just eighteen months she lasted. No virgin, Katherine Howard was charged with treason |

|

Catherine Parr Now a cynical and dispirited man, And martyr to a fierce temper, there began The final, erratic phase of his long reign. The old goat decided to marry again. Another child bride would be going too far, So this time he settled for Catherine Parr: Twice widowed, trustworthy and amiable – To be honest, the best choice available. A Protestant, but non-political, The children loved Catherine, not just because |

|

EDWARD THE SIXTH (1547 – 1553) Edward the Sixth was pious and haughty, Precocious and a prig. Never naughty, He was self-assured, formidably bright, Protestant, proud and always in the right. Sorry to speak so ill of the young chap, Some will say his heart was in the right place. Chantries were dissolved, where masses were said Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, Cranmer’s new version was spectacular. Edward was consumptive (we call it TB) |

|

MARY TUDOR (1553 – 1558) If Mary Tudor had played her cards right, She might have gone far. Her prospects were bright. Though plain, she was popular. More inclined To mercy than vengeance, she was refined, Gentle and intelligent. She sang well, With a fine contralto voice, I hear tell. But the people were in for a rude shock. England was in a state of mortal sin. After Edward, this came as a volte-face. Thirty-seven years old when she came to the throne, Thomas Cranmer had managed King Henry’s divorce Between Cranmer and the steadfast Catholic Queen. Then, having been found guilty (this bit makes me sick), |

|

At the stake he confounded the powers-that-be By denouncing the Pope’s usurped authority, Whereupon he put his right hand into the flame: “This hand,” he cried, “hath offended. The very same “Should be the first to be consumed.” So Cranmer died. News of his heroism travelled countrywide, ‘Bloody’ Mary, then, the Queen came to be called. However, England’s worst fears were realised In June ’57 England declared war: The bells rang out to mark poor Mary’s death, |

|

ELIZABETH THE FIRST (1558 – 1603) Elizabeth the First was made of steel, Yet still commanded popular appeal. Striking of countenance, with flame-red hair, She proved herself her father’s one true heir. Milksop Edward and the frightful Mary Here she differed from her father. The waste, Henry the Seventh (you know I’m a fan) Elizabeth, though, was nobody’s fool. Hardly the best of starts… Her step-mother |

|

EXECUTION OF MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS Mary Stuart’s sad life was drawing to a close. In 1586 (quite how, nobody knows) Francis Walsingham unearthed the Babington Plot. Whether he ‘set it up’, as some claim, I know not, But Mary was led to believe, somehow at least, That with the help of God, and the odd friendly priest, She could safely correspond with plotters abroad – In France. This was a folly she could ill afford. Walsingham intercepted her correspondence – Read her every rash, unguarded utterance. This plot, like the rest, would place Mary on the throne, Parliament, People, Council – all were as one: The stumbling block was Queen Elizabeth the First, February the 8th, 1587, |

|

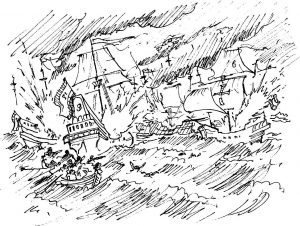

THE SPANISH ARMADA The seminal events of 1588 – If you remember anything, make it this date – Were a milestone in the fortunes of the nation. They marked, moreover, a thorough vindication Of the Queen’s foreign policy: preparation, Over decades, for war; naval reparation; And a secure kingdom, of her own creation. On July the 19th the Spanish were sighted The Spanish plans lacked basic co-ordination. On July the 28th, approaching midnight, The bad weather helped, but leadership was the key. News of our victory only reached the nation |

|

Although her body was a weak and feeble thing, She had, she said, “the heart and stomach of a King” – Moreover, she professed, “a King of England too”. And, though the persons present numbered but a few, Her words were learned by heart by subjects yet unborn. That “any Prince should dare invade” she thought “foul scorn”. The borders of her precious realm were sacrosanct, And so it proved. England was saved. May God be thanked. The Spanish fleet limped home. Half at the very most |

| LITERATURE AND MUSIC The great golden age of Gloriana Saw a flourishing of the arts: drama, Poetry, music. William Shakespeare – The dramatist supreme and sonneteer – Led the field. Elizabeth was a fan. The fine tradition of blank verse began, And achieved perfection in Shakespeare’s plays. |

|

His fellow writers are worthy of praise: Kit Marlowe, stabbed to death in mid-career In a pub brawl, in his thirtieth year; Thomas Kyd, his plays all blood and thunder, Who died deep in debt, and little wonder. Marlowe and Kyd were promising playwrights, Though both, in their way, over-fond of fights. The most rare Church music you’ll ever have heard To name the painter of the age is not hard: In King Henry’s time, the masters of verse More accessible still is the sonnet. “How may the poet turn his sharpest wit |

|