Volume Five – 1660 – 1685

Charles the Second and the Restoration

CHARLES THE SECOND’S TRIUMPHANT RETURN

CORONATION

QUEEN CATHERINE

THE GREAT PLAGUE

THE GREAT FIRE

THE NEW ST. PAUL’S

NELL GWYNN

THE POPISH PLOT

DEATH OF KING CHARLES THE SECOND

CHARLES THE SECOND’S TRIUMPHANT RETURN

Charles’ royal progress stretched over four days.

The splendour! The pomp! The towns were ablaze!

From Dover and thence to Canterbury,

Then Rochester, his popularity

Was palpable, patent and plain to see

At Blackheath he encountered his Army,

‘Introduced’ by Monck. Where did power lie?

Good question. It was hard to deny

That George was firmly in the driving seat.

Or was he? Best to keep the old man sweet.

Butter him up, let matters take their course

And never, ever, try to rule by force.

So the King entered London. His birthday,

By happy chance, fell on that favoured day:

Thirty years old – the 29th of May.

Charles took full advantage, as was his way,

Of this fitting coincidence. I’d say

(Were I asked) it was timed to perfection.

Stage-managed? Have you any objection?

If people are starved of spectacle, fine –

Let ’em have it! The fountains flowed with wine.

The Venetian Ambassador (stout chap)

Offered a regular supply, on tap.

Bottoms up, Venice! It took seven hours

For the royal procession to pass. Towers,

Walls, balconies – all were bedecked with flowers;

The streets hung with banners and tapestries;

Companies all in their finest liveries,

With the Mayor and Aldermen, if you please,

In chains of gold; windows “well-set” with ladies;

Heralds, footmen and lackeys; noble lords, clad

In rich cloth of silver and velvet. Not bad,

I’d say, for a people so lately deprived

Of colour and show. They seem to have survived!

You think I’m embroidering? Take a look

(It’s well worth it) at John Evelyn’s book,

His Diary. The detail, it’s all there.

An acute eye-witness, writing with flair,

His account is astonishing. The din,

Above all, as described by Evelyn,

Is what, three and a half centuries on,

Endures. The actors are long dead and gone,

But hear the hubbub! Folk are still “shouting

“With unexpressable joy… bells ringing,

“Ladies, trumpets, music… ” with crowds “flocking

“The streets… ” And in the midst of this, one man,

Silent, reflecting how it all began.

“I stood in the Strand,” John Evelyn writes,

“And beheld it” (his report still excites)

“And blessed God.” A miracle, plain to see:

The King restored, “by the very army

“Which rebelled against him”. It was, truly,

“The Lord’s doing”. Who are we to disagree?

It was, indeed, “past all human policy”.

Back to top / Buy the book

CORONATION

As you would expect, the King’s coronation

Was a great event that inspired the nation.

This took place in April, 1661 –

On the 23rd, to be exact. The sun

Shone that day (St. George’s Day). The bishops wore

Gold copes. At Westminster Abbey (the west door),

Charles was met by nobility by the score,

The peers in their robes, holding their coronets.

Fine anthems were sung. No one was placing bets

On the length of his reign. Yet, on this glad day,

Old, unhappy memories were stashed away,

As his Majesty made his way to the throne.

With no Queen, he must have felt rather alone.

Not that he showed it. Charles was in his element.

He heard the Bishop of London ask all present –

“Lift up your hearts!” he cried – whether they would accept

Charles for their King or no. The tender-hearted wept.

Four times they shouted, “God save King Charles the Second!”

His coronation was generally reckoned

One of the grandest (and most costly) of all time.

I feel privileged to celebrate it in rhyme.

The King was anointed. Well, he had to be –

That was the key point of the ceremony.

His waistcoat was opened “in divers places,”

Evelyn tells us (they loosened the laces,

I imagine). The Bishop “commodiously”

Anointed the palms of his hands, for all to see;

Then his breast; then “twixt the shoulders”; then, finally,

The “crown of his head”. You almost feel you were there,

An eye-witness. Then they smoothed down the royal hair

As the Imperial Crown was placed on his head.

The peers of the realm knew their place, it has to be said.

Only now did they don their coronets. A ring

Was slipped, with reverence, on Charles’ finger. Singing

Of more anthems followed, music with viols, lutes

And trumpets. The choir, in their best Sunday suits,

Led a rendition of the splendid Te Deum.

There were republicans who cursed the tedium

Of this ritual; who hoped for that happy day

When this royalist nonsense would be swept away.

But these disappointed spoilsports, with good reason,

Were given the cold shoulder, well out of season.

His Majesty received the Holy Sacrament –

Another sore point if you harboured discontent –

Before sailing, by “triumphal barge”, to Whitehall,

Where extraordinary feasting crowned it all.

The next day John Evelyn presented the King

With “his panegyric”. It does set one thinking:

All that praise; that flattery. A pretty cool head

Had the King. He was a man not easily led,

For he knew his own mind and he died in his bed.

Back to top / Buy the book

QUEEN CATHERINE

The King’s choice fell on Catherine of Braganza,

From Portugal. Something of a bonanza

Was the huge dowry that the Infanta

Brought to the table. Charles couldn’t have cared less,

Of course, for her wealth – though, I have to confess,

He was reported “very much affected”

When her assets were listed! As expected,

He found the three hundred thousand pounds (in cash)

Not unpalatable. He’d have been most rash,

Rash indeed, to have turned his back on Bombay

And the port of Tangier (though, I have to say,

The latter caused many a headache). One day,

If I’ve time, I’ll have more to say about that.

The Infanta was tiny, like a wee bat,

But not unappealing. She was twenty-three

(On the old side), renowned for her piety

(On the plus side), and, though she had sticky-out teeth

(On the plain side), it was Charles’ confirmed belief,

Once he had seen her, that she’d nothing in her face

That “can shock one”. In short, she was no disgrace.

In fact, the King thought her eyes were “excellent good”.

If anyone would do for a Queen, she would.

Catherine arrived in May ’62.

A Catholic consort was nothing new.

Few could remember (curious, but true)

Anyone else but a Catholic Queen.

Anne of Denmark was Protestant – had been,

At least (James the First’s long-suffering wife),

Before she converted early in life.

Anne kept her head down. Her daughter-in-law

Was the opposite, though. This I deplore.

Henrietta Maria, Charles’ mother,

Was vastly unpopular – oh, brother!

The King and his new bride were ‘married’ twice:

A Catholic service to break the ice

(To satisfy the Queen), in secrecy,

Private and necessarily low key;

Then a full, Protestant ceremony,

Open and plain for the people to see.

Catherine brought an ample retinue

Of Portuguese servants (well, wouldn’t you?):

Ladies-in-waiting (ugly as sin

The lot of them, of ancient origin),

Monks, dressmakers, acrobats, hairdressers,

Cooks, dancing-masters, father-confessors…

For reasons that will later become clear,

This rag-bag of attendants (dear, oh dear)

Didn’t last long. But what’s important here

Is that the Infanta tried, from day one,

To live the English way. Everyone,

From the start, admired the Portuguese Queen –

Well, not Barbara Palmer, as we’ve seen,

Nor Andrew Marvell, the poet. I mean,

To call the Queen “a goblin” – how obscene.

I had high admiration for Marvell.

A fallen poet. How tragic. Ah, well…

The Queen arrived at last at Hampton Court

On the 29th of May. Now this ought,

By rights, to have been a merry event.

For Charles paid Catherine the compliment

Of welcoming her ‘home’ on his birthday,

Co-incident with the very same day,

Two years before, as his Restoration.

Evelyn was there. His fascination

Shines through. He notes the “monstrous fardingals”

Of the “Portuguese ladies” (the Queen’s pals) –

All “sufficiently unagreeable”

(The ladies, he means). Unforeseeable,

To Evelyn, was how short a time they’d last!

Portraits suggest that Cath had a slight cast

(Or so it looks to me) in her right eye,

Yet John singles out (and I wonder why –

I have to say, it comes as a surprise)

Her fine “languishing and excellent eyes”.

As for her hair, she wore “her foretop long” –

The Portuguese way, though I could be wrong –

“And turned aside very strangely”. She changed,

However, within weeks. Her hair’s arranged,

In all her pictures, in the English style.

She quickly proved herself an Anglophile.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE GREAT PLAGUE

Plague had ever lurked in London’s crowded streets,

Its narrow lanes and byways, its dark retreats,

Its busy passages, its wide, stinking drains

And open sewers. From what one ascertains,

There was no connection drawn (bizarre, but true)

Between hygiene and disease. Let me tell you,

I’m glad to be living in a later age.

The Plague, just imagine… Read on, down the page…

Pepys again is our day-to-day eye-witness:

Seven months of danger, terror and distress.

June the 7th Pepys jotted in his Diary:

“The hottest day that ever I felt.” Fiery,

Blistering, it was London’s dire misfortune

That the summer was such a scorcher. ‘Flaming’ June

Gave way to record temperatures in July,

And then through August into September. That’s why,

Alas, the awful Plague was able to take hold,

The worst instance of the pestilence, so we’re told,

In London’s history. Pepys, on this fateful day,

Was strolling, no care in the world (as was his way),

Down Drury Lane, when he spotted (alackaday)

“Two or three houses marked with a red cross”, the first

“To my remembrance”. Samuel feared the worst.

Red crosses on the doors! The capital was cursed!

June the 10th Pepys reports (more’s the pity)

“That the Plague is come into the City”.

Worse still, it had fetched up in Fenchurch Street,

In the house (Pepys’ heart must have missed a beat)

Of Dr. Burnett, his neighbour and friend.

The good Doctor contemplated his end,

Alone. According to his chum’s record,

He shut himself up “of his own accord”.

One hopes that virtue reaped its just reward:

Most generous to his neighbours, and some!

As Pepys comments aptly, “very handsome”.

By immuring himself, the Doctor, no doubt,

Was hoping the pestilence wouldn’t get out.

The authorities later enforced a law

That infected families (mainly the poor,

Inevitably) should be made to remain

Boarded up in their houses. Picture the strain,

The stress, the despair, as they waited for Death,

Clawing at the walls till their very last breath.

The rich and the powerful (this I deplore)

Evaded this cruel (though practical) law,

By fleeing to the country. Need I say more?

What else, they would argue, was affluence for?

Pepys, like Evelyn, his fellow diarist,

Stayed in the City, a point that’s often missed.

No, to be fair, towards the end of the year

Pepys decamped out of London. But with the fear,

The uncertainty, and the ever present

Dread of infection, who are we to resent

His decision? What people did find galling

Was the conduct of the Court: quite appalling!

The Queen ‘emigrated’ to Salisbury,

And when one of her grooms’ wives (poor woman, she)

Succumbed to the disease, they set off again,

For Milton – Queen, Court and her entire train.

Charles, fair to say, remained in London longer,

Together with James, both fitter and stronger.

I do have to say, this was reckless and rash.

He was King, after all, and didn’t lack cash.

Cowardice in the mighty is never nice,

But for Charles to die? A senseless sacrifice.

June the 14th One hundred and twelve died

“This last week”. The figure, a rising tide,

Compared with forty-three the week before.

For forty-six long weeks Pepys kept a score,

The increase in numbers terrifying.

Yet he moved in the midst, death defying!

June the 17th Pepys was in a coach –

His bravery is far beyond reproach,

Given the patent risk of infection –

Driving in an easterly direction,

Down Holborn, when the coachman suddenly

Was “struck very sick” so “he could not see”.

Pepys switched coaches (quite understandably),

Dreading the Plague. This was how it began,

With a sneeze and falling sickness. The man,

Pepys feared (a witness to his sudden fit),

Was “struck with the Plague”. Would he now catch it?

A mass exodus from London began,

By coach, by wagon, by barge. Some just ran!

John Evelyn stayed for the duration.

A hero, he never left his station

As Charles’ commissioner for the care

Of sick and wounded prisoners. Despair,

Panic and cowardice were not for John.

As the Plague raged about him, he pressed on,

Loyal, determined, with a job to do

In the King’s service. He trusted (would you?)

“In the prudence and the goodness of God”.

A dangerous path John Evelyn trod.

He reports that he passed “coffins exposed

“In the streets”. It can only be supposed

That he was fearless. Upright and devout,

He walked untouched, all too aware, no doubt,

Of his mortality, yet well prepared

To meet his Maker. While others despaired,

He wrote (with an eerie objectivity)

Of the “mournful silence” and, ominously,

“As not knowing whose turn might be next” – and this

At the height of the pestilence; hit or miss

Whether a man lived or died; two thousand dead

In a week. Where most folk of quality fled –

Even Pepys, at the Plague’s worst, as we’ve noted –

Evelyn, bless him, stuck it out, devoted

To the King’s cause. I’m pleased (and relieved) to say

That once the threat abated (oh, happy day!)

Our hero was introduced to the King.

Charles ran to greet him (highly gratifying),

Offered his royal hand to kiss and, with grace,

Thanked his good servant for his care in the face

Of such manifest peril. So, no disgrace!

Back to top / Buy the book

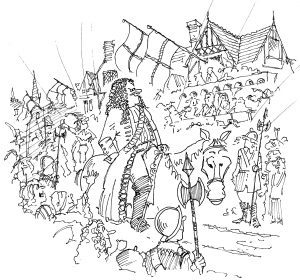

THE GREAT FIRE

“One entire arch of fire” Pepys now saw,

“Of above a mile long”. He watched in awe –

Nay, horror: “It made me weep to see it.”

The only recourse was flight. So be it.

Yet Pepys hurried back to his own abode,

The fire by now not far from his road.

He bore some of his best goods “by moonshine”

Into his garden. These would include wine,

I’d hazard (even periwigs?). Well, fine,

Why not? His money and his “iron chests” –

Officials in those days feathered their nests –

He moved to the cellar, the safest place

Should his house be destroyed; and, just in case,

He gathered together his bags of gold –

To take to his office (or so we’re told).

The following morning, at four o’clock,

He sent for a cart to remove his ‘stock’ –

His plate, all his money and his “best things” –

To Bethnal Green. The comings and goings

Were a sight to behold, with all the town

On the move – and Pepys still in his nightgown,

In that cart! The mind boggles. Proud? Not he,

So long as his goods were stashed securely.

Evelyn again: September the 3rd.

His report that day is to be preferred

To Pepys’. The latter is pre-occupied

(Who can blame him? I’d have been petrified)

With his own safety. Again from Bankside,

John saw “the whole south part of the City”,

All of London, ablaze (oh, the pity)

From Cheapside to the Thames, along Cornhill

And, “kindled back” by the south-east wind still,

Now consuming Tower Street, Fenchurch Street

And Gracious Street. This was a mere heartbeat,

Scarily, from Pepys down in Seething Lane –

A fact that goes a long way to explain

His personal forebodings on that day.

I’d have shared his terror, I have to say.

The heat seemed somehow to “ignite the air”,

Contriving (quite creepy this), to prepare

The materials to “conceive the fire”.

The fierce wind, as we’ve seen, sought to conspire

With the arid season. The conflagration

Brought upon people a “strange consternation”;

There was “crying out and lamentation”;

And, according to John’s computation,

The “clouds… of smoke” reached “fifty miles in length”.

Our own best eye-witness (his greatest strength),

Evelyn notices that “all the sky

“Were of a fiery aspect” (oh, my…)

“Like the top of a burning oven”. Night –

“If I may call that night” – became daylight,

Can you believe, “for ten miles round about”.

It surely wasn’t only the devout

Who feared the wrath of God. John had no doubt.

“A resemblance of Sodom” so it was,

“Or the last day” – and this surely because

No other image sufficed. “London was”

(Mark Evelyn’s sombre words) “but is no more.”

Two square miles the fire consumed. Oh, lor!

And still that’s only on the second day.

On September the 4th, sorry to say,

The news was no better. Oh, by the way,

I missed from my account of yesterday

The loss of St. Paul’s. The fire took hold

As the flames were fanned westward. The “scaffolds,”

John wrote, “contributed exceedingly”

As fire consumed the Church, greedily.

Back to top / Buy the book

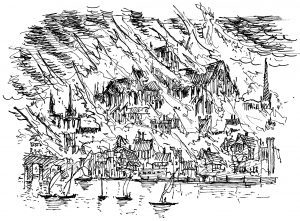

THE NEW ST. PAUL’S

No words can render justice to St. Paul’s.

Take your time, but when inspiration calls

Witness the wonder for yourself. The Dome –

Comparable to St. Peter’s in Rome –

Is three hundred and sixty-five feet high.

Sorry to bang on. It’s one reason why

St. Paul’s is so famous. This will amaze:

Over sixty-five thousand tons it weighs.

In his old age (he died at ninety-one)

Wren would return to St. Paul’s, his work done,

And sit under his great Dome, to reflect –

And offer up thanks to God, I suspect.

Christopher Wren was a hands-on architect.

It was he who supervised the craftsmen,

Hired the stonemasons and carvers, often

From abroad. One such, commended to Wren,

Was Grinling Gibbons, wood carver sublime.

John Evelyn, polymath of his time,

‘Discovered’ Gibbons “in a poor… thatched house”

In Holland. No craftsman could carve a mouse,

A leaf or a twig with such dexterity,

With such a “loose and airy lightness” as he.

Sir Christopher (as he became) would, weekly,

Inspect his creation from a basket. We,

Of course, now consider this curiously quaint.

But hauled up and down on a pulley? Safe, it ain’t!

Many there were who feared that the great weight

Of the Dome would cause its collapse. Its fate

Became the subject of fevered debate.

On the day the scaffolding was removed,

Wren (the King would surely not have approved)

Watched the great unveiling from the high spot

Of Parliament Hill. Like it or not,

Should the Dome ‘implode’, he’d be gone that day

(His carriage was waiting), off and away!

Imagine: his reputation in tatters.

But St. Paul’s stood the test. That’s all that matters.

Back to top / Buy the book

NELL GWYNN

“Pretty, witty Nell” (as described by Pepys:

The middle-aged lech, he gives me the creeps)

Was on the stage by the age of fourteen.

A “bold, merry slut” she may well have been

(Pepys again, can you believe?), she was ace

In comedy. Not just a pretty face,

She had perfect legs and delicate feet,

Was impertinent, wild and indiscreet.

The King was enraptured. They chanced to meet

In the dying days of Barbara’s reign,

Confirming the end of old Castlemaine.

Nelly was seventeen (eighteen at most).

Her earlier lovers, she liked to boast,

Embraced two more Charleses. So ‘Charles the Third’

The King became! She was saucy, my word!

She coined other wonderful nicknames too –

James, Duke of York: ‘Dismal Jimmy’. She knew

That Charles wouldn’t mind. He laughed like a drain,

Returning for more again and again.

One rival, Louise de Kéroualle, asked why

She was dubbed ‘Squintabella’. Nell was sly:

Sadly, Louise had a cast in one eye.

Like Barbara P, Lou liked a good cry

(That is, she threw temper tantrums) and so

She became, for her pains, ‘Weeping Willow’!

Nelly’s wit and sense of humour were priceless.

Not necessarily renowned for ‘niceness’,

She was famous for her ready repartee.

The mob occasioned her some anxiety

At Oxford, mistaking Miss Gwynn for Louise.

They jostled her coach, attacking, if you please,

The bitch they declared to be Charles’ Catholic

Harlot. Such naked prejudice makes me sick,

But, ever in high spirits, Nell saved the day.

Sticking her head out of the coach window, “Pray!”

She cried, “Good people, be civil!” (this I adore –

So witty, so sharp) “I am the Protestant whore!”

Back to top / Buy the book

THE POPISH PLOT

Fear of Catholics was utter rot.

Here in England, though, like it or not,

The stage was set for the Popish Plot.

August that year was very, very hot,

With London as oppressive as it got.

One Titus Oates, a thoroughly bad lot,

And Israel Tonge (a dangerous clot)

Hatched a most frightening conspiracy.

Since there was no plot, in reality,

They set about to invent one. The King

Was to be murdered – whether by stabbing,

Shooting or poisoning was left unclear,

But never mind. The Pope, it would appear,

Was behind it, the odd Catholic peer,

And the Archbishop of Dublin (oh, dear),

With Louis of France bringing up the rear!

Amazingly, Tonge and Oates were believed.

It’s astonishing how much they achieved

By sinister lies and innuendo.

They simply sowed the seeds and watched them grow.

Papists were unpopular. Even so,

It still appears quite staggering to me

That the ‘plot’ developed quite so lethally.

Rome was the Antichrist. Couldn’t folk see?

The age-old Catholic conspiracy

Was alive and well, in the here and now.

The Papists were on the warpath, and how!

The Great Fire of 1666 –

Who started it? Catholic fanatics!

The Duke of York, no shadow of a doubt,

Lit the first fuse. (He helped to put it out,

You’ll recall). Even the prosecution

Of Charles the First, and his execution,

Formed part of the Catholic ‘solution’.

The anti-Catholic tradition

Ran deep. The Protestant position

Was, by contrast, robust and strong, and yet

Men feared for their lives. The Catholic threat

Was real, pressing and immediate –

In their eyes. One description of the time

Demonstrates this lunacy in its prime.

I’m hard pressed to transpose it into rhyme,

But here goes: “your children torn… limb from limb”

Or “tossed upon pikes” (I said it was grim)

And “your wives prostituted to the lust

“Of every savage bog-trotter”. Just?

You must be joking! Naked prejudice…

“Your daughters ravished” (now listen to this)

“By goatish monks… Your own bowels ripped up”

(Could this be written in true earnest? Yup!)

With “your dearest friends flaming in Smithfield”.

Papists’ revenge! The Protestants’ fate sealed!

Lastly, “holy candles made of your grease”:

I like to see that as the centrepiece.

Forget “the joyful sounds of Liberty”,

For “this, gentlemen, is Popery”.

So where was the hard evidence? Nowhere.

There was none. And nobody seemed to care.

Fear played its part. Believe this if you will:

Parliament decreed (a bitter pill)

That anyone with the temerity

To question the plot’s authenticity

Did so in danger of his life. Justice?

I don’t think so. Pure, naked prejudice.

Back to top / Buy the book

DEATH OF KING CHARLES THE SECOND

During the night of February the 1st,

1685 (a date forever cursed),

The King, according to reports, tossed and turned.

His man, Thomas Bruce, expressed himself concerned

That a huge wax candle that had brightly burned

Extinguished itself without a breath of wind.

Ominous, he felt. The King was thicker-skinned

And, after a hearty supper of goose eggs,

Turned in. He had a pain in one of his legs

And spent, as I’ve hinted, an unsettled night.

The picture on the 2nd was none too bright.

His face was ashen, with bags under his eyes,

His tongue a dullish brown. It was no surprise

That his speech was slurred and his vision impaired.

The doctors were puzzled; young Thomas was scared.

But for what happened next they were unprepared.

Seated in his closet (his normal routine)

For his daily wash, Charles turned a shade of green,

Slumped forward and let out a terrible scream.

Dr. King (who heard it) rushed in with his fleam

(His blood-letting lancet), a pretty close shave,

And bled his royal majesty. This was brave.

He’d have been tried and hanged as a scurvy knave

Had the powers-that-be had a mind to it.

Charles’ blood could only be drawn (and King knew it)

With the clear and specific authority

Of the Privy Council. Did he care? Not he!

This was a clear-cut, royal emergency.

The Council, it appears, agreed. King had grounds

For the bleeding. His reward: one thousand pounds.

Evelyn notes that Charles took fine delight

In his “little spaniels”. These, at night,

He suffered to snuggle into his bed.

The bitches gave suck (the puppies were fed)

Under the covers. It has to be said

That John was probably right to complain

Of the smell. It must have stunk like a drain!

Watch then as Charles the Second spreads his wings

And soars towards the bosom of his Lord.

No Nelly there? I trust he won’t get bored.

Back to top / Buy the book