Volume Nine – 1760 – 1789

George the Third and the Loss of America

GEORGE THE THIRD, A POPULAR START

MARRIAGE AND CORONATION

WEDGWOOD POTTERY

A VISITOR FOR DR. JOHNSON

‘FARMER GEORGE’

THE BOSTON TEA PARTY

CHARLES JAMES FOX

OLIVER GOLDSMITH

DAVID GARRICK

THE KING’S RECOVERY FROM MADNESS

GEORGE THE THIRD, A POPULAR START

When the old King died (sadly, on the loo),

It was out with the old, in with the new.

The prospect of a youthful, virile King

Was a breath of fresh air, a touch of spring.

His manner was “graceful and obliging” –

This from, of all people, Horace Walpole.

Tolerably good-looking, on the whole,

His reign was something of a watershed.

For George was the first monarch born and bred

In England since the time of good Queen Anne.

Despite the late Queen’s nickname, ‘Brandy Nan’,

Her fragile popularity, bless her,

Eclipsed that of her German successor,

George the First, and his son, George the Second,

Both brought up in Hanover, and reckoned

Far too ‘European’ for their own good.

Now here was a better George who (touch wood)

Promised otherwise. For he spoke plainly:

“Born and educated in this country,

“I glory in the name of Britain.” See?

This explains his early popularity.

Back to top / Buy the book

MARRIAGE AND CORONATION

The King was single and needed a Queen,

German and Protestant, know what I mean?

George was impatient and not too choosey.

Not that he’d plump for any old floozy,

But his coronation was beckoning

And a King, he knew, by any reckoning,

Should swear his oath with a wife by his side.

The search was on. It was time to decide.

Europe was scoured for foreign princesses,

Favouring those with German addresses.

Several candidates were rejected

As too intelligent, the respected

Frederica of Saxe-Gotha for one.

She read books of philosophy for fun.

That, in a nutshell, was simply not done:

This free-thinking woman was far too bright!

Another contender (still not quite right)

Was Philippina of Brandenburg-Schwedt.

In some respects the most promising yet,

She had a short fuse, I’m sad to report,

A snappy, ill-tempered, quarrelsome sort.

The King’s requirements were simple: good sense

And good nature over intelligence.

Looks counted for less, though a pretty face

And acceptable hair were no disgrace.

Above all else, his Queen should prove her worth

As fit for breeding and for giving birth.

The choice fell on a seventeen-year-old,

Neither tall nor a beauty, so we’re told

(By Horace Walpole). The lucky lady,

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, maybe,

Just maybe, was what George was looking for.

And so it proved. She had a solid jaw,

Fleshy nostrils that flared, and a low brow.

I’m sorry, I make her sound like a cow.

Far from it. She had good teeth, fine dark hair

And a pleasing demeanour. Have a care,

Those of you who pick a bride sight unseen.

You could do worse than the King with his Queen.

True, Charlotte was no looker. Thin and pale,

Though genteel and sensible, she was hale,

Nonetheless, and hearty. Her eyes were bright

And she enjoyed a healthy appetite.

Sociable and lively from the start,

Charlotte had an open, generous heart.

She spoke no English, bless her cotton socks,

But proved herself a little chatterbox.

Her French was passable, if hit and miss.

Her love of music made amends for this.

She played the harpsichord (as did the King),

The glockenspiel to boot. Charlotte’s singing

Was charming. She sang at her own wedding,

Unbidden. This ceremony took place

On the very night (a perfect disgrace)

Of her arrival in England. Charlotte

(I salute her) gave as good as she got.

Just as well. Folk laughed themselves into fits

At the mere thought of Mecklenburg-Strelitz,

A lowly, north German duchy – the pits.

‘Muckleburg-Strawlitter’ the wags called it.

Sarcasm is the lowest form of wit,

And this Charlotte knew. Poor she may have been,

But she excelled herself as England’s Queen.

Guess how many children she had? Fifteen!

I kid you not. She more than satisfied

The King on this score, it can’t be denied.

Charlotte’s North Sea passage was rough. Oh, lor –

She’d never set foot on a ship before.

The crossing lasted a week and a half.

Neptune, quite clearly, was having a laugh.

Diverted to Harwich, two days it took

To travel to London. In anyone’s book,

This was a journey to jangle the nerves.

To give her the credit Charlotte deserves,

She arrived serene and wondrously cool.

The girl, it appears, was nobody’s fool.

George showed no trace of dissatisfaction

At first sight of his bride. His reaction,

Rather, was one of studied solicitude.

In an age where manners inclined to the crude,

All credit to the King. In generous mood,

He made no comment on Charlotte’s appearance,

Giving thanks to God for her safe deliverance.

Her arduous journey notwithstanding,

Poor Charlotte was forced to share with the King

(And his mother) a seven-course banquet.

I mean, how insensitive can you get?

One hour later (you’ve heard nothing yet)

She was married. That’s right! At ten o’clock!

They’d hastily run up her wedding frock

From measurements sent over from Strelitz –

A gorgeous gown, with velvet pockets,

A cap studded with diamonds, a crown

Bedecked with jewels. She was so weighed down

By her train (and her own heart-heaviness?),

How she bore the strain is anyone’s guess.

She was near to fainting. “Courage, Princesse,”

Urged the Duke of York, brother to the King,

As he squeezed her hand. It’s astonishing,

To me, how Charlotte kept a level head.

But she plighted her troth. “Ich will,” she said.

After more feasting it was time for bed.

Few grooms have ever felt quite as well fed

As the young King. Stuffed, it has to be said.

The couple didn’t get to bed till four.

It’s awkward showing wedding guests the door,

But the new Queen was insistent (mark this)

On resisting the ancient practice

Of admitting mothers (and other guests)

To the bridal chamber. Charlotte’s protests

Were accepted with ill grace. This suggests,

In one of such limited experience,

A liberal helping of honest good sense.

Be that as it may. The following night,

At the royal ball, George took clear delight

In his fair Queen. He never left her side.

He loved her to bits and he glowed with pride.

Two weeks later came the coronation.

This rich and spectacular occasion

Took place on September the 22nd

And was, by report, generally reckoned

To have strengthened the King’s reputation.

George earned the respect and admiration

Of all his assembled subjects present

By removing his crown (like a true gent)

Prior to receiving the Sacrament.

Truly, no King in British history

Swore his oath with more reverence than he:

To uphold that age-old institution,

Namely the Protestant constitution.

Moves towards Catholic emancipation,

Late in his reign, led to the resignation

Of his trusted Prime Minister, William Pitt

(The Younger, that is). The old King was obdurate.

George would honour the plain words that he had spoken.

He was adamant. His oath was not to be broken.

A footnote. During George’s coronation

A heavy jewel (to the consternation,

Evidently, of the whole congregation)

Fell out of his crown. In hindsight, the nation

Saw this as an ill omen – in the seventies,

When Britain lost her American colonies.

Back to top / Buy the book

WEDGWOOD POTTERY

Josiah Wedgwood’s famous pottery

Was one early beneficiary

Of the canal network. His factory,

Built at Etruria (between Hanley

And Newcastle-under-Lyme), was handy

For the new canal connecting the Trent

And the Mersey. Its fragile wares were sent

By barge. Better than carts, no argument –

Bumping along old, rough, pitted roadways.

Josiah’s practice was beyond all praise.

At Etruria (a first for those days)

He designed a village for the workers.

Wedgwood, we’re told, had no time for shirkers,

But he offered a good deal. Tough but fair,

He set great store by employee welfare.

A rudimentary insurance scheme

He launched for sick-benefit. No daydream:

Wedgwood achieved the best from his workplace.

Hard graft and strong profit – where’s the disgrace?

Capitalism with a human face.

With business partner Thomas Bentley

Josiah elevated pottery

To a noble art. Fame he won worldwide

With his ‘creamware’, and was near deified

For his vases, of classical design:

Novel in concept, elegant and fine.

These compelling artefacts caught the eye

Of Queen Charlotte, who was inspired to buy

From Wedgwood. His ‘Queen’s ware’, as it was called,

Set a trend. Society was enthralled.

The renowned Catherine the Great, no less,

Empress of Russia, sealed his success

By commissioning from Josiah –

I can think of no compliment higher –

A complete dinner and dessert service

Of one thousand pieces. Some order that is!

The delicate work took four years to complete,

But completed it was. The Empress could eat

Off the best. The service is now on display

In St. Petersburg. You can see it today

At the Hermitage Museum, a rare treat.

As the trip of a lifetime it’s hard to beat.

Back to top / Buy the book

A VISITOR FOR DR. JOHNSON

Men of letters were afforded access

To the King’s Library. George’s largesse

Even extended, as one might expect,

To men for whom he had little respect.

Those with distasteful political views

(Whigs) and non-believers (very bad news)

Were welcome. The King would never refuse.

Dr. Johnson was a staunch Royalist.

He was most certainly on the King’s list

Of those fine scholars whom he wished to meet.

Both men, it appears, were in for a treat.

The good Doctor’s heart must have skipped a beat

As he chanced to look up from his studies

To find none other than George, if you please,

His Majesty the King, his sovereign,

Standing there. Johnson jumped out of his skin.

“Sir,” said the librarian (whispering),

As Sam gathered his wits, “here is the King!”

The Doctor was honoured. The King had come,

Specifically, to meet him. Struck dumb?

No, far from it. According to Boswell,

Johnson recovered remarkably well.

He spoke to the King “with profound respect”,

Not in the “subdued tone” you would expect

At the levée, but in a manly voice,

“Sonorous” and “firm”. A sensible choice,

And one praised by Dr. Goldsmith, his friend,

Who feared he himself (he couldn’t pretend)

Would have “bowed and stammered”

through the whole thing,

And made a poor impression on the King.

George was relaxed, far from condescending.

There was no blushing, bowing or scraping,

For the King, like all interesting folk,

Showed a keen interest. This is no joke.

For Johnson, a highly erudite bloke,

Was scholarly, wise, accomplished and shrewd.

The King was eager (without being rude)

To pick his brains. It’s as simple as that.

George had the common touch. I’ll eat my hat

If ever he was proud, haughty or grand.

He soon had Sam in the palm of his hand.

What was the Doctor currently writing,

Enquired the King? Anything exciting?

Johnson’s response was rather surprising:

He wasn’t undertaking anything.

He’d already told the world all he knew.

He had nothing more to contribute. Phew!

The King replied, “I should have thought so too,”

(Mark this) “if you had not written so well”.

You can see how Sam fell under his spell.

This compliment, Johnson was wont to say,

With some pride, “was fit for a King to pay”.

To George’s fine words he made no reply.

Sir Joshua Reynolds once asked him why.

“No, sir. When the King had said it,” said he,

“It was to be so. It was not for me

“To bandy civilities” (splendid phrase)

“With my Sovereign.” Johnson took the praise,

But, wrote Boswell, “with a dignified sense

“Of true politeness”. For this, in essence,

Is why the exchange was so successful:

A true meeting of minds, nothing stressful,

Nothing awkward, just a conversation –

To the good Doctor, a revelation.

They spoke of other scholars of the day,

Such as Dr. Hill, of whom, by the way,

Johnson had precious little good to say.

The Doctor would never pretend, you see.

The two even touched on philosophy,

Before a request from his Majesty

For a literary biography

Of the country, to be written, perforce,

By Johnson himself. Samuel, of course,

Signified his readiness to comply.

It was never written, I don’t know why –

A cause for regret, it’s hard to deny.

Johnson was highly taken with the King,

Not only for George’s depth of learning,

But also for his manners, which were those

“Of as fine a man as we may suppose

“Lewis the Fourteenth or Charles the Second”.

The King’s Library itself, Sam reckoned,

Was a collection more “numerous” –

I was tempted to say ‘voluminous’ –

And “curious” than one might have surmised.

Johnson, indeed, was impressed and surprised

That any one man could have realised

This feat in the time that George had employed.

The myth has been well and truly destroyed

(I hope) that the King was a philistine.

He’ll continue to have his detractors, fine,

But I’m glad to report they’re in sharp decline.

A brief footnote. In 1823

George the Fourth gifted the King’s Library

To the nation. One stipulation

Of the new King’s generous donation

Was that the books should be kept on display

To the public, which they are to this day.

You doubt my word? Then visit, I urge you all,

The British Library. There, in the Front Hall,

Towards the rear, is the bottom storey

Of a book tower which, in all its glory,

Stretches the entire height of the building.

Like a long glass bookcase, it’s astonishing –

And it houses the books of my favourite King.

As the trip of a lifetime it’s hard to beat.

Back to top / Buy the book

‘FARMER GEORGE’

The King was ‘Farmer George’ too, don’t forget.

Country folk and farm workers whom he met

Were much struck by his generosity,

His easy air of informality.

Meeting a pig boy in Windsor Great Park,

George was upset to hear the boy remark

He had no work. Young boys were not required.

The likes of him, he said, were never hired.

The King was all ears and asked him why.

Because all the farmland, came the reply,

Belonged “to Georgie”. Georgie was the King

Who lived in the Castle, and did nothing.

George, of course, arranged immediately

For the lad to have employment. To me,

There’s no better proof of his humanity.

Hundreds of acres went under the plough

In Windsor Great Park. There are farms there now.

The King took a personal interest

In seeing they yielded only the best.

He even wrote under a pseudonym –

‘Ralph Robinson’, yes, was really him –

In Arthur Young’s Annals of Agriculture

On the subject, I think (I cannot be sure),

Of the rotation of crops. George took pride

In touring his farms, with Young at his side,

Stressing the finer points of their upkeep,

And pressing Young on questions of sheep,

Grasses and crops. Young found fault, if you please,

With his hogs. No criticism of these,

However, would the King accept. A gift,

They were, from the Queen and she might be miffed.

Back to top / Buy the book

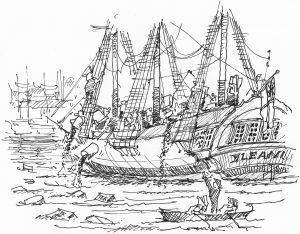

THE BOSTON TEA PARTY

The day was the 16th of December,

A date Bostonians still remember.

The year? Yes, 1773.

Tea from the East India Company

Was sitting in ships in Boston Harbour:

The Dartmouth, the Beaver, the Eleanor.

The ‘British’ Massachusetts Governor,

Thomas Hutchinson (the mug), insisted

The tea come ashore. This was resisted.

Stout Tom refused to return the cargo:

The consignment must be unloaded. No,

Cried the patriots! This was stalemate. So,

Led by Samuel Adams, they boarded

The vessels. History was rewarded

With one of its most exciting of scenes.

Hutchinson, one of its many has-beens,

Was aghast when up to sixty Mohawks –

Armed, for all I know, with their tomahawks –

Stormed the ships at anchor in the harbour.

With spirit and rebellious ardour

They cast the tea chests overboard. The waste!

Tea may not be to every fish’s taste,

But they partook of the party that day –

The ‘Boston Tea Party’. Anchors a-weigh!

The Mohawks were colonists in disguise.

This shouldn’t come as any great surprise.

The Brits, of course, were very, very cross.

Purely in financial terms their loss

Was some eighteen thousand pounds. The true cost,

However, was the trust and credit lost

Between the two parties: the colonists,

Increasingly seen as separatists,

And (in George’s phrase) the ‘Mother Country’.

The stage was set for a showdown. Sadly,

There were to be tears, agony, bloodshed –

To the shame of all, it has to be said.

Back to top / Buy the book

CHARLES JAMES FOX

Charles James Fox, wit, gambler and debauchee,

Was a true ‘one-off’. No time-server he,

Fox voiced the most virulent abhorrence

Of the King. He showed little tolerance

For convention. His clothing was soiled

And scruffy. As a lad, he’d been badly spoiled

By his father, Henry. As a callow youth,

His manners were lazy, rude and uncouth.

He could do no wrong by his doting dad.

Much of the money poor old Henry had

Was spent in discharge of his son’s bad debts.

Wherever gentlemen were placing bets,

Charles was sure to be found. Before his death,

Old Fox stumped up the vast sum (hold your breath)

Of one hundred and forty thousand pounds

To pay off Charles’ debts. The figure astounds.

In Rockingham’s ill-fated government

I gather that Fox had been well content

To serve George as Secretary of State

For Foreign Affairs. Shelburne was third-rate,

In his considered opinion, so

Fox was prepared to let the whole world know

That where Shelburne favoured a guarded line

He (Fox) would be happy to countersign

Any agreement, in the King’s presence,

Granting America independence –

Up front, then and there, no pre-condition!

This served to frustrate Shelburne’s ambition

To keep the vital independence card

Up his sleeve – woefully, in this regard,

The sole available ace to be played.

George, of course, was similarly dismayed

By Fox’s conduct. Enough was enough,

But his hands were tied. Then, in a great huff,

Fox resigned. The spoilt child again, you see…

Serve under Shelburne? It wasn’t to be.

An insult! A monster indignity!

The King was rid of Fox at last. Hurrah!

Young William Pitt, the fast-rising star,

Became Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Cast now as dissident and arch-wrecker,

Charles James Fox was content to bide his time.

Let no one tell him he was past his prime.

He’d be back. As indeed it proved. Meanwhile,

Shelburne, First Lord, with genius and style,

Grasped the nettle of the peace. At long last

Even George recognised the die was cast.

Back to top / Buy the book

OLIVER GOLDSMITH

Johnson wrote of Goldsmith: “His genius

“Is great, but his knowledge is small.” Bless us,

That’s a back-handed compliment. But wait:

“Goldsmith was a plant that flowered late.”

She Stoops to Conquer answered perfectly,

To Sam’s mind, “the great end of comedy” –

Namely, “making an audience merry”.

High praise. The play has stood the test of time.

Oliver, too, excelled himself in rhyme.

The Deserted Village, his masterpiece,

Is a joy and (will wonders never cease?)

He wrote a fine novel, still read today –

The Vicar of Wakefield. Sorry to say,

The manuscript was sold for sixty pounds,

Well under value – though Johnson had grounds

For claiming to have procured a fair price

On Oliver’s behalf. To be precise,

Goldsmith had written to Sam, confessing

To heavy arrears of rent – distressing

And dreadful. Johnson sent him a guinea,

Promising to come himself directly.

Upon his arrival, what did he find?

Goldsmith’s landlady (the harridan kind)

Had apprehended her tenant for debt.

Poor Ollie, confused and gravely upset,

Had spent the Doctor’s life-saving guinea

On a bottle of madeira. Calmly,

Johnson put the cork back in the bottle,

Then, with the wisdom of Aristotle,

Discussed ways in which the debt could be paid.

Goldsmith, still more than a little dismayed,

Produced a novel, ready for the press,

For his friend to consider. It’s my guess

That Sam’s surprise was as great (if not more)

As the landlady’s. Off to the bookstore

He hurried (satisfied of the book’s worth)

To sell the manuscript. Thus he ‘gave birth’

To The Vicar of Wakefield, selling it,

As you’ve heard, for sixty pounds. He saw fit

To agree this sum, given the dire state

Of Oliver’s affairs. At any rate,

Goldsmith presumably gave his consent.

The novel was sold and he paid his rent.

The most modest of men, and always poor,

He died deep in debt in ’74.

Cheerful in company and generous

(To a fault), Oliver could be nervous

And unforthcoming. Surprisingly vain,

He cut a clumsy figure. He was plain,

Awkward and shy. “No man” (Johnson again)

“Was more foolish when he had not a pen

“In his hand” (Sam was the bluntest of men)

“Nor more wise when he had.” I’ll eat my hat

If Goldsmith wouldn’t have settled for that.

Back to top / Buy the book

DAVID GARRICK

Garrick was acclaimed at an early age –

A mere twenty-two when he took the stage

As Richard the Third at Drury Lane.

The course of his life’s career was plain:

Young David could conjure a storm! His Lear

Was a tour de force, though a little queer,

It has to be said, was his choice of dress:

A short, ermine-trimmed robe (odd, I confess),

With tight white silk stockings and buckled shoes.

The public loved it, reserving their boos

For his Othello, in full black make-up

And Moorish attire – this a rare hiccup.

For Garrick, in Boswell’s words, was “pure gold”,

Excelling in comedy, so we’re told,

As well as the darkest of tragedies.

The talent of an actor was to please,

According to Johnson. “Harmless pleasure”

Was “the highest praise”. Sam had his measure.

Garrick, “the cheerfullest man of the age”,

Spurned the immorality of the stage,

A “decent liver” in a profession

Given to licence. That’s some concession.

Free with money and faithful to his wife,

He led an upright and a blameless life.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE KING’S RECOVERY FROM MADNESS

On St. George’s Day a service of thanksgiving

To celebrate the recovery of the King

Was held in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Fox was booed

By the vast crowd lining the route, a trifle rude,

True, but fully deserved. The Prince of Wales was hissed

In his coach, a sure sign he would never be missed.

Pitt had played a blinder. The people were content

To acclaim him to the skies wherever he went.

The day, however, belonged to the King.

6,000 children had been taught to sing

Psalm One Hundred, orphans of the City.

At this George wept in his infirmity.

Some saw him as an object of pity.

His face was thin; he’d lost three stone in weight;

There was apparent weakness in his gait.

The King had readily professed to Pitt

That he still felt edgy and far from fit.

When asked, though, how he expected to cope

At St. Paul’s, his answer gave cause for hope:

He had twice read the accounts of his case,

Against which an event as commonplace

As a three-hour service of thanksgiving

Was hardly likely to throw him. Some King!

Indeed, his Maj. was seen to chat away

With the Queen as if he’d been at a play.

He brought his opera glasses! But hey –

If George had a ball, good for him, I say.

His two elder sons, on the other hand,

Behaved disgracefully. Ill-mannered, grand

And arrogant, they cracked jokes and sniggered.

The crunching of biscuits also figured –

During the sermon. All this in public!

Small wonder the Queen was heartily sick.

Looking back, this has a comedic ring.

In truth, it did little harm to the King.

George’s new surge in popularity,

Born of his opportune recovery,

Made Britain safe for a generation.

Across the Channel, France was a nation

In crisis. There the wretched King and Queen

Would soon lose their heads to the guillotine.

A reign of terror? Couldn’t happen here.

Or could it? No! Prosperity… good cheer…

The British people had nothing to fear.

King George the Third (that’s ‘Farmer George’ to you)

Was worthy and honest, steadfast and true.

If the French lost the plot, what could you do?

Trust in William Pitt! But that, as they say,

Is another story for another day.

Back to top / Buy the book