Volume Four – 1649 – 1660

Cromwell and the Commonwealth

OLIVER CROMWELL AND REGICIDE

CROMWELL’S AUTHORITY

CROMWELL’S RETURN FROM IRELAND

THOMAS FAIRFAX

THE BATTLE OF WORCESTER

THE LORD PROTECTOR

RELIGIOUS TOLERATION

CROMWELL’S ILLNESS AND DEATH

THE RETURN OF KING CHARLES THE SECOND

OLIVER CROMWELL AND REGICIDE

King Charles the First (from the books that I’ve read)

Was defiant in death. He lost his head,

One swift stroke of the axe, before a crowd

Of anguished spectators, who groaned out loud.

Not for them the accustomed jubilation

Of a public execution. The nation

Stood in sorrow, shock, confusion and despair.

You couldn’t find a subject anywhere,

Outside the Levellers (all half barmy),

Fifth Monarchists, and some in the Army,

Who hailed the murder as a deed well done.

The regicide, a crime second to none,

Was justified without recourse to law,

The trial a farce: justice by the back door.

Cromwell rued the King’s death. How could this be?

Ever Charles’ political enemy,

In battle his principal adversary,

He pursued him to trial with energy.

He signed the death warrant, the third signatory,

Yet, over the body, “cruel necessity!”

Were the words Cromwell uttered. It has to be said,

He considered the dangers of Charles the First dead

As great, if not greater, as Charles the First living.

I’m not saying Cromwell was soft or forgiving,

Yet he tried for a settlement – oh, how he tried!

But his efforts were thwarted, his struggles denied,

By the King’s double-dealing. I took Charles’ side,

But his cunning and lies, I have to confess,

Quite altered my views. Now I couldn’t care less.

The crowned heads of Europe (hardly a surprise)

Were struck with horror at the late King’s demise,

And the manner of it. How safe were their heads?

Did their own fates hang by the thinnest of threads?

How likely were they to be slain in their beds?

Politics were politics. The regicide,

Though abhorred and awful, could not be denied –

Tantamount to political suicide

To ignore. Cromwell came to be much admired

As the years rolled on. His example inspired.

Back to top / Buy the book

CROMWELL’S AUTHORITY

Throughout the Interregnum, year on year,

The truth would become abundantly clear:

Cromwell was the Guv’nor. Why shed a tear?

Without his talent and his vision,

His hatred of drift and division,

England would ever be under the yoke

Of Kings and tyrants, no word of a joke.

The Irish, of course, will never agree –

But they’ve genuine cause, as soon you’ll see.

Underpinning Cromwell’s authority,

Of course, all decade long was the Army.

This was the uncomfortable reality.

There existed a deep-seated antipathy

Between Army and Parliament, its pedigree

Stretching back to the heady days when the late King

Would play one off against the other, indulging

In the time-honoured tactic of ‘divide and rule’.

For Oliver Cromwell was nobody’s fool.

He struggled to hold the balance for years –

Many predicted it would end in tears –

Between the Rump (the purged Parliament)

And the Army. It was effort well spent.

There were limits, of course. If something had to give,

He would round on the Rump (far too conservative),

Paying due regard to the Army’s frustration

At the lamentable pace of change. The nation

Wanted the firmest authority to save it.

Strong leadership was needed. Oliver gave it.

Cromwell was at heart a facilitator –

Radical, yet an arch-conciliator.

He remained a master, to his dying day,

Of the art of the possible. I must say,

For a man renowned for getting his own way

He was skilled in the subtleties of compromise,

And far more pragmatic than many realise.

Unafraid to confront the more radical factions

In the Army, and undaunted by the reactions

Of his own colleagues, he was nevertheless

A fair man and generous – hence his success.

Back to top / Buy the book

CROMWELL’S RETURN FROM IRELAND

Oliver, not before time, was recalled

In May 1650. He was appalled.

He’d started the job, he was fighting fit,

He’d prefer to stay out to finish it.

But a conflict with the Scots was brewing,

A powder keg (this the young King’s doing).

Oliver was needed, his expertise,

His flair. Ireland, already on her knees,

Was all but conquered. Wasted overseas,

Cromwell returned, leaving his son-in-law,

Henry Ireton, to pursue the war.

The Irish campaign continued (it’s true)

For three more years – till 1652.

England’s hero was lauded like no other man

Since the story of our proud islands began.

That is something of an exaggeration

(You’ll have spotted that), but the entire nation,

Rich and poor, high and lowly, young and old,

United in his praise. Heroic, bold,

Courageous… A day of thanksgiving

Was announced. The Irish, less forgiving,

Remained, as like as not, silent that day.

The poet Andrew Marvell had his say:

“ ’Tis madness to resist or blame

“ The force of angry heaven’s flame. ”

So Cromwell’s campaign was immortalised

In his Horatian Ode. I’m surprised,

Indeed touched, by the poet’s awareness

Of the late King’s plight. His sense of fairness

Is compelling. Charles “bore his comely head”

(Vintage Marvell) “down as upon a bed”.

Tender words for an arch-republican

And future MP for Hull. Quite a man.

Speaker Lenthall rose in Parliament

And spoke of Cromwell as “God’s Instrument”.

A telling phrase. We should respect Lenthall.

His words, dear reader… Well, they say it all.

Back to top / Buy the book

THOMAS FAIRFAX

Thomas Fairfax was never fully reconciled

To the King’s foul murder. A man who rarely smiled –

Take a look at his portrait, by William Fairthorne –

A more melancholy fellow had never been born.

Tall, swarthy (as a boy, ‘Black Tom’ was his nickname),

Sir Thomas (as he then was) won eternal fame,

At a critical juncture of the Civil Wars,

Battling for the Parliamentary cause.

Bravely he fought at Naseby in particular,

And later, courageously, at Colchester.

Fairfax was a moderate, though, in this regard:

Parliament served as the King’s “greatest safeguard”

Against his enemies. He saw in monarchy

The best bulwark against chaos and anarchy.

When called to serve on the Bench at the King’s trial,

He stayed away. Some thought he was in denial.

Not so. Fairfax was appalled at the whole process.

When his name was read out, Lady Fairfax, no less,

(In disguise, but it was she) exclaimed without fear,

Behind her mask: “He has too much wit to be here!”

No fool, Sir Tom! Yet he declined to intervene

In a plot to rescue the King. Nor was he keen,

To say the very least, on the sentence of death.

He appealed on Charles’ behalf. He wasted his breath.

Don’t infer from this that Fairfax was a weak man.

Hardly. But from the moment the trial began,

Events moved with inexorable energy.

All a man of honour could do, it seems to me,

Was sit out this sad, lamentable tragedy.

Fairfax was a true servant of the republic

For its first two years. The King’s murder made him sick,

But Thomas was nothing if not realistic.

As we’ve seen, he avoided the Irish campaign.

His loss (if that’s the right word) was Oliver’s gain.

Now he retired altogether to Nunappleton,

In Wharfedale. I wouldn’t exactly claim he had fun.

Consider that portrait! But he relished private life,

Looking after his horses, spending time with the wife –

Not, of course, in that order. Tutor to his daughter

Was Andrew Marvell, the poet. Just what he taught her,

I’m not exactly sure. But Fairfax could have done worse.

For Marvell composed some of his very finest verse

During his sojourn in Yorkshire (or so I’d suggest) –

The Garden, for example, surely one of his best:

“Society is all but rude

“To this delicious solitude.”

This could only have been penned in a secluded place,

Where withdrawal from the wider world spelt no disgrace.

“Stumbling on melons, as I pass,

“Ensnared with flowers, I fall on grass.”

The swollen imagery! The voluptuousness!

The most noble of poets, I’m obliged to confess.

So be it. Let’s leave him with Fairfax, his employer,

And rejoin Cromwell, warrior and destroyer.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE BATTLE OF WORCESTER

‘Charles the Second’ (self-styled) took the western route

Down through England. He needed now to recruit.

His ambition was to attract to his lists

Battalions of discontented Royalists.

Alas, it never happened. Charles got it all wrong.

Far from augmenting his force as he went along,

His progress was marked by a strange disinterest,

Inertia and cowardice. Put to the test,

The royalist party proved itself unready,

Uncommitted, unsupportive and unsteady.

Cromwell shadowed the King. Just enough rope

He gave him to hang himself. Charles, the dope,

His forces outnumbered by two to one,

Fetched up in Worcester. A man on the run,

He stood not a chance. His army was tired,

Demoralised, hungry and uninspired.

Cromwell took the decision to attack

Rather than lay siege. Though the King fought back,

With ferocity, the cause was soon lost.

He defended the city at huge cost:

Over 3,000 Royalists were slain.

To what purpose? I’m sure I can’t explain.

Their bodies piled up in the alleyways,

Dead horses too, like one of those old plays,

Where corpses litter the stage in Act Five

And nobody seems to be left alive.

But this wasn’t fiction, this was for real.

For me, such drama holds little appeal.

As for the lead actors, how did they feel?

Charles fled the field. He was lucky, I’d say,

To escape with his life. As was his way,

He made light of the matter. Merry, yes.

How he survived… Well, that’s anyone’s guess.

He took to his heels. He was young and fit.

An oak tree, they say, played a part in it.

Inn signs to this day (this isn’t a joke –

I dare say you’ve seen some, ‘The Royal Oak’)

Commemorate the occasion. Well said.

Less ominous than his dad’s pub, ‘The King’s Head’.

Worcester was fought on the 3rd of September,

Exactly a year to the day, remember,

Since Dunbar. They say that superstition

Dictated the date. Cromwell’s position,

Outside Worcester, on the 2nd was strong.

He delayed for a day (I could be wrong)

To ensure that the battle fell on the date

Of his victory at Dunbar. Well, that’s Fate –

Or is it, if the whole thing is pre-arranged?

There’s an odd legend (was Oliver deranged?)

That he led one of his captains, on the 3rd,

To a wood, where they met (I know it’s absurd)

A strange old man who promised Cromwell, then and there,

That he’d “have his will” for seven years, then – despair!

Crazy, I know. Till I tell you (you have my word)

That Cromwell breathed his last on September the 3rd,

Just seven years later, in 1658.

It appears that the hermit told Oliver straight!

Be that as it may, Cromwell’s great victory

Fully cemented his place in history.

He returned in triumph. “Our Chief of Men,”

John Milton hailed him. England cried, “Amen!”

Back to top / Buy the book

THE LORD PROTECTOR

From December the 16th, ’53,

Cromwell would sign himself ‘Oliver P.’ –

Oliver Protector. Events had moved

With lightning speed. Cromwell was approved

(By whom? That’s a well-directed question)

As Lord Protector. There’s no suggestion

That he sought the crown. King Oliver? No.

Cromwell was sensible enough to know

That the Army would never have worn it.

Nor would Royalists at large have borne it.

And Cromwell’s objective, as we shall see,

Was to foster peace and stability,

Reconciliation and harmony.

His inauguration ceremony,

Having said that, reeked of regality.

Oliver was soberly dressed, in black,

But the pageant around him took folk back

To the coronations of yesteryear,

Where splendour and pomp raised many a cheer.

His only concession to frippery

Was a deep-gold hat band! His modesty

Was palpable. His air of gravity,

His sense of purpose and solemnity,

Were manifest and plain for all to see.

The ancient emblems of monarchy

Set off his natural simplicity.

The Protector was appointed for life.

‘His Highness’, Cromwell became; his good wife,

Elizabeth, the ‘Lady Protectress’.

They moved to a wildly fancy address,

Whitehall Palace. Cromwell couldn’t care less

For pomp and show, though I have to confess

He did look forward to his weekend haunt,

Hampton Court, whence he would savour a jaunt

To Bushy Park for his recreation –

Hunting and hawking. His reputation

As a spoilsport was quite unjustified.

For Noll had a warm, convivial side.

He loved music. This must be qualified.

Music in a religious context:

Definitely ‘out’. But any pretext

To enjoy it as a secular art –

Proof, if need be, that he did have a heart –

Singing, for instance, was most surely ‘in’,

As was chamber music. It was no sin

To relish melody. The violin

(I’ve read this) grew in popularity

During the Protectorate. So you see,

He was no Philistine. A committee

Was even constituted (since you ask)

For the advancement of music. The masque –

The rage, you’ll recall, in the old King’s day –

Crept back into fashion, though the stage play

Was outlawed during this period. Dance,

Tending to vice and popular in France,

Was tolerated up to a degree

Within the bounds of strict morality.

Back to top / Buy the book

RELIGIOUS TOLERATION

One policy greatly to Cromwell’s credit

(Often ignored, so I’m glad to have said it)

Was that of religious toleration.

His interest in a unified nation

Was best served by keeping to a minimum

State interference. Only the troublesome

(Such as the Quakers) or the more quarrelsome

(Such as the Ranters) or the more meddlesome

(Such as the Fifth Monarchists) were kept at bay.

Their anti-social views, I have to say,

Rendered this disruptive fringe beyond the pale.

The Protector fought these zealots tooth and nail,

Though even Oliver (bless his cotton socks)

Would engage the Quaker leader, one George Fox,

In private debate. Cromwell was a sinner,

Declared George over an intimate dinner!

He even struck up (though this sounds fantastic)

An earnest friendship with a great Catholic,

Sir Kenelm Digby. This was rated a sin

By that irate Puritan, William Prynne.

But Cromwell relished Sir Kenelm’s company

And inclined to an engaging clemency

Towards Catholics. Freedom of conscience

Was Oliver’s ideal. It simply made sense.

It should still not be forgotten, however,

That under the law Catholics would never

(I repeat, never) enjoy the liberty

To express their faith freely and fearlessly.

In practice, though, little was done to enforce

The anti-Catholic laws unless, of course,

There was evidence, or even suspicion,

Of mischief, rebellion, plots or sedition.

In addition, Cromwell re-admitted the Jews

To England. His Council held different views,

But he simply overruled them. Good for him!

This sound policy wasn’t made on a whim.

The Jews had been driven out as long ago

As 1290, a most bloody blot, I know,

On England’s historical record. Cromwell,

Never loth to deliver the odd bombshell,

Recognised their value and, down to this day,

The race has proved him right, I’m happy to say.

Back to top / Buy the book

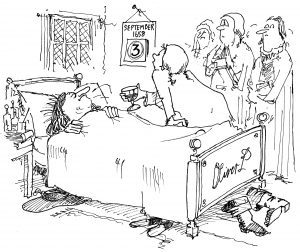

CROMWELL’S ILLNESS AND DEATH

An old hermit predicted (remember?)

Long before, on the 3rd of September

(1651), that on the same day,

Seven years on, Oliver would die. Hey,

It’s a good story. Superstitious rot,

Cry the historians. Like it or not,

On the anniversary of Dunbar,

And Worcester too, Noll Cromwell, superstar,

Was called to Heaven to meet the good Lord.

Some coincidence! You can ill afford

To be completely cynical, you know.

Cromwell enjoyed no choice. He had to go

When Fate decreed. Not so very absurd

To take the aged hermit at his word.

What was the cause of death? Malaria,

Picked up in the general area

Of Ireland, scene of his famous campaigns?

The illness (one of its more gentle strains)

Was not uncommon in those far-off days,

Plaguing its victims in various ways –

Sweating and fever, distemper and fits,

Enough to drive a man out of his wits.

To kill him, though? Yes, perhaps. But Cromwell

Had recovered before, so I’ve heard tell,

So why not again on his deathbed? Well,

As I’ve hinted, his resistance was low,

He was old… In short, we shall never know.

Ollie suffered too from the dreaded ‘stone’,

Which was hugely painful, that much is known.

They discovered his spleen livid with pus

When they opened him up. He made no fuss,

Brave to the last. He placed his total trust

In the Lord his God, as he knew he must.

He named his successor, but only just!

His Secretary of State, John Thurloe,

Was one of many who needed to know.

He feared deep divisions, and that’s a fact,

Were Cromwell to die without an heir. Tact,

However, and more than a little fear

Prevented him bending the old man’s ear.

His boss was in a state of denial,

I’d hazard. It wasn’t Oliver’s style

To raise the mirror to mortality.

He was forced to confront death, finally,

By his Council, of which a select few

Forgathered at his bedside (they all knew)

And mooted the name of his eldest son,

Richard. This didn’t please everyone,

But Cromwell assented. So it was done.

“Heaven’s Favourite!” Who could disagree?

Andrew Marvell: spot on. His poetry

Was in a state of sad decline, frankly,

But his lines on Noll’s death, his elegy,

Contain fine words of rare simplicity:

“Valour, religion, friendship, prudence died

“At once with him, and all that’s good beside.”

I’m a fan. You can tell. It’s no surprise

That this perfect verse brings tears to the eyes.

There’s more, much more. Forgive me if I quote.

Marvell’s a wonder, a poet of note.

“I saw him dead. A leaden slumber lies

“And mortal sleep over those wakeful eyes.

“Oh human glory vain, oh death, oh wings,

“Oh worthless world, oh transitory things!”

Unless Marvell saw him on his deathbed –

Oliver the man, actually dead –

These verses are something of a fiction.

I’m loth to be the one to cause friction

In poetic circles, but the truth is

Cromwell’s body caused a terrible tizz.

They botched the embalming procedure. Pooh!

The smell was quite horrid, I’m telling you.

His body was buried without delay

In Westminster Abbey where, to this day,

It should have lain at rest, unmolested.

Yet, though his allies strongly protested,

He was dug up at the Restoration –

Such was the level of detestation –

Carted (along with Ireton and Bradshaw,

Both long dead too, you had better be sure)

To Tyburn, where the corpse was hanged. His head,

As if to prove he was properly dead,

Was hacked off and later spiked on a pole,

Where it stayed rotting for years. On the whole,

I think poor Noll deserved a kinder fate.

His skull did find its way, at any rate,

In recent years, back to his old college,

Sidney Sussex, Cambridge. To my knowledge,

Only a select few know its whereabouts,

To protect it from vandals and lager louts.

Marvell might have observed his effigy,

Lying in state for all the world to see,

At Somerset House, in great majesty.

As royally accoutred as could be,

Oliver had more the air of a King

In death (ironic) than ever living.

For three glorious weeks he lay in state –

His waxen image did, at any rate –

This in accordance with age-old practice.

Most dead Queens and Kings were decked out like this,

For public inspection. A royal crown

They placed on his head. Cromwell turned it down

In life. Dead, it appears he had no choice –

Hardly, I’d venture, a cause to rejoice.

Back to top / Buy the book

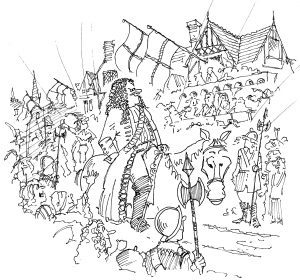

THE RETURN OF KING CHARLES THE SECOND

And so it was that at the end of May

Charles made ready. The King was on his way.

On the 29th (the royal birthday)

He rode into London. The bells rang out.

Some 20,000 men (or thereabout)

Attended their sovereign. Fountains flowed

With wine, all the day long. Lining the road,

In their finest array, the people cheered,

As their long-awaited monarch appeared.

The famous diarist, John Evelyn, wrote

(His words are perfect, it’s best if I quote):

“I stood in the Strand” (an eye-witness, you see)

“And beheld it and blessed God” (then, touchingly)

“And all this without one drop of blood”. Rarely,

If ever, can a moment in history

Have been captured with such sensitivity.

So began what’s generally reckoned

The dissolute reign of Charles the Second.

The King’s considered a perfect disgrace –

By some. Not by me. Kindly watch this space.

Back to top / Buy the book