Volume Twelve – 1859 – 1901

The Later Victorians

QUEEN VICTORIA AND POOR ‘BERTIE’

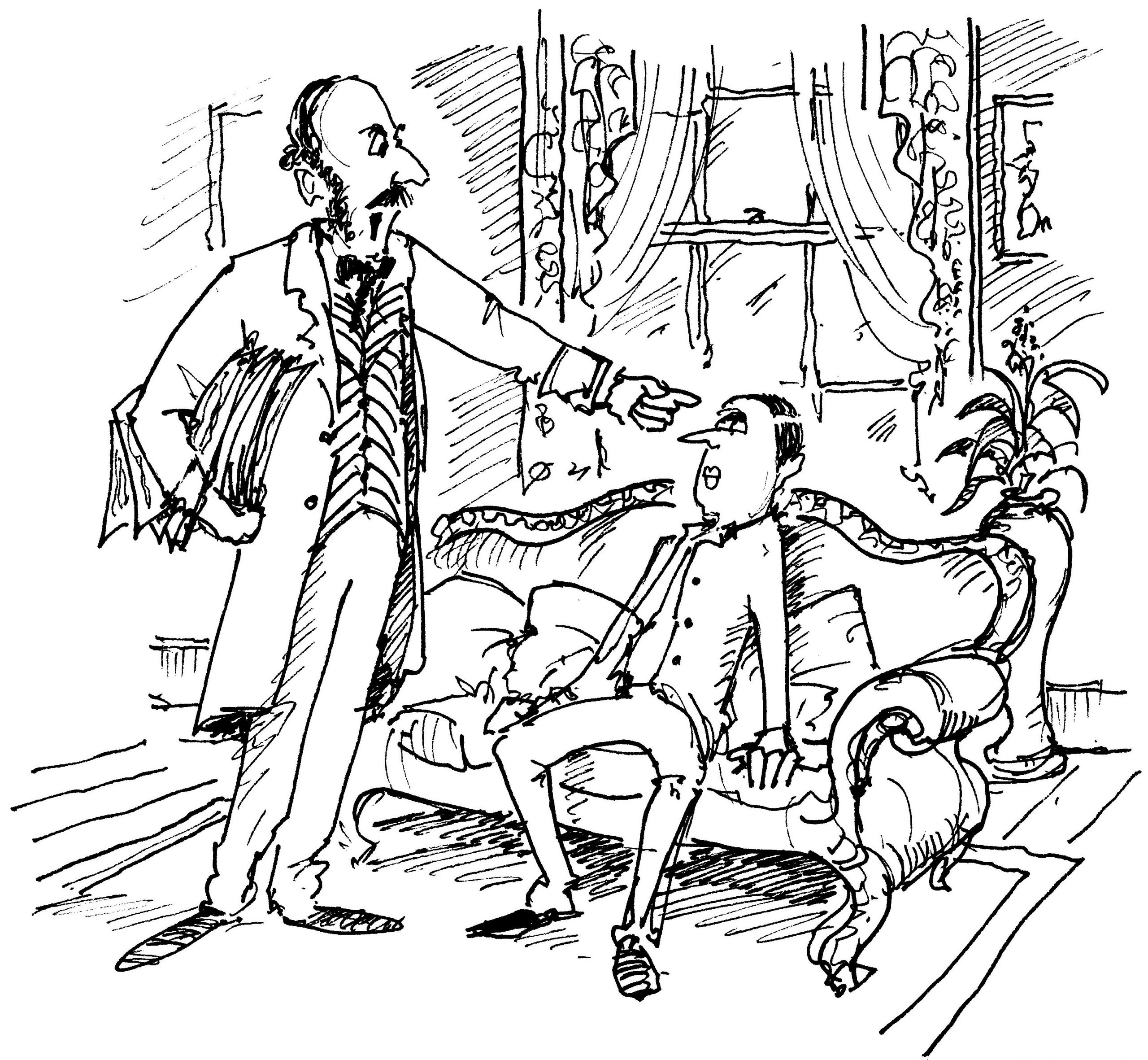

THE ALBERT MEMORIAL

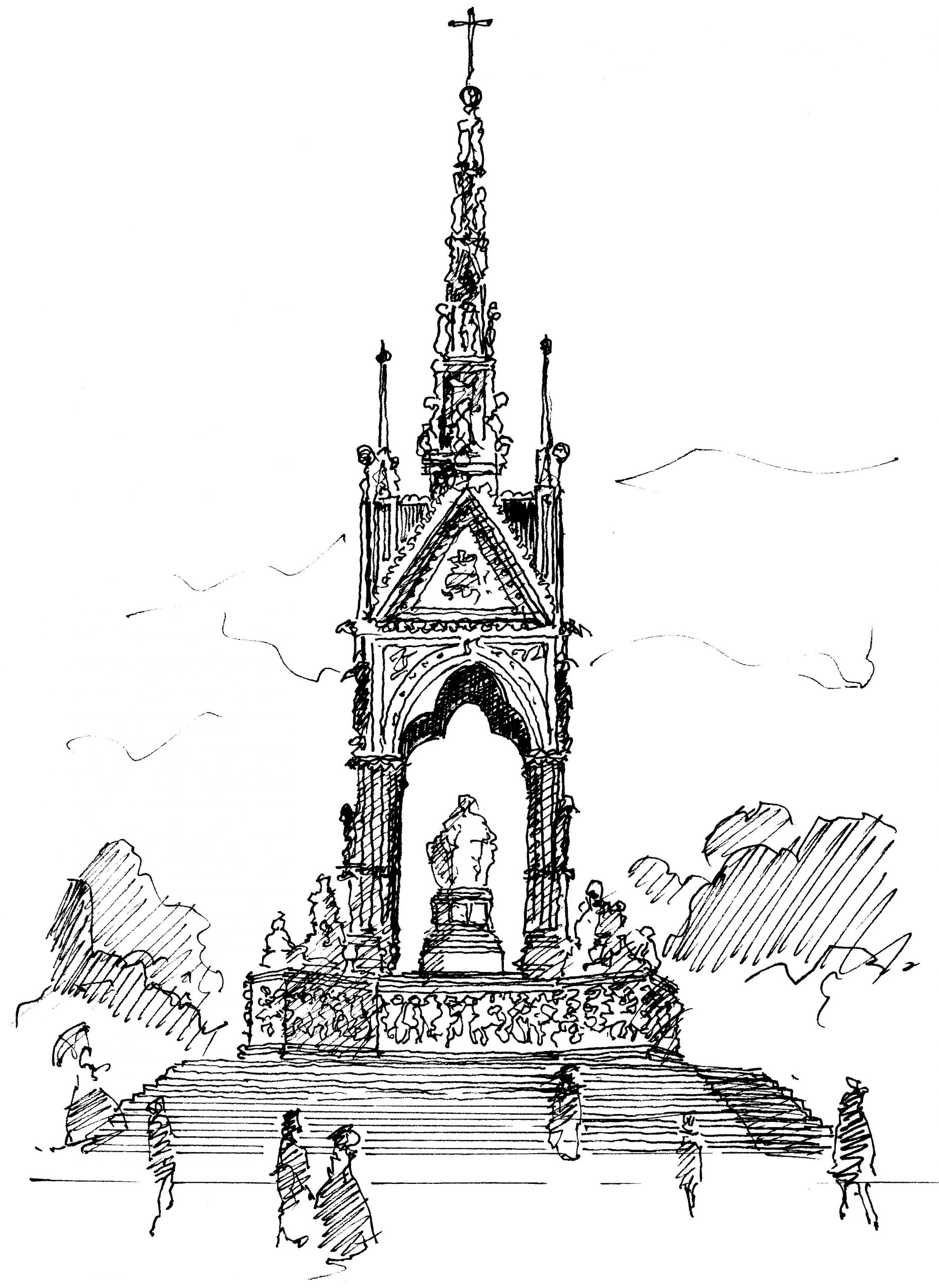

MRS. ISABELLA BEATON

MUD-LARKS

EMPRESS OF INDIA

THOMAS BARNADO

ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON

THE VICTORIAN AGE

EDWARD THE SEVENTH

QUEEN VICTORIA AND POOR ‘BERTIE’

Enjoying her share of laughter and tears,

The Queen had reigned for twenty-one years,

Roughly one third of her allotted span.

I’ll never profess to being a fan,

But admit to admiring her courage.

She suffered an early disadvantage,

Under the thumb of the Duchess of Kent,

Her sour mama, full of discontent

And bitter spleen. The instant she was Queen,

She threw off the shackles. A mere eighteen,

She was quick to learn, hardworking and keen.

Modest by nature, and no great beauty,

Her firm resolve was to do her duty,

A mission rare in earlier times.

A hot temper was the worst of her crimes.

This perhaps (there is no way of knowing)

Explains the spirit that kept her going.

Albert was her anchor, her love, her life.

As a monarch, a mother and a wife,

She made mistakes, as surely you’d expect,

For she lacked experience. Circumspect?

No. Considered and cautious? Barely.

Yet her aim was ever to act fairly,

With justice and honour. It was Bertie,

The Prince of Wales, who drove her to despair.

Antipathy towards her son and heir,

In true Hanoverian tradition,

Was sadly the Queen’s default position.

‘Poor Bertie’, as she labelled the young chap,

Suffered grievously from the handicap

Of meddling parents. Idle and weak

(Victoria’s view), his future looked bleak.

Game for a laugh and non-academic,

He was lazy (true) and apathetic

When it came to the slog of book-learning.

His sister Vicky was more discerning.

She alone saw the good in her brother,

Capable (as she wrote to her mother)

Of true affection, warmth and feeling.

Albert’s lectures left the poor boy reeling –

History, architecture, art, the lot…

Culture, the classics… He cared not a jot.

Nor was it only a matter of books.

The Queen was scornful of her young son’s looks.

“His nose and mouth” were “enormous,” she said,

And he “pasted his hair down to his head.”

Some mother! “He really is anything”

(She did not mince her words) “but good-looking.”

Poor Bertie, indeed. It gives me pleasure

To report that in time, for good measure,

Edward the Seventh, as the lad became,

Was a popular King. He won acclaim

For his open heart and his relaxed style,

Trumping his mother by a country mile.

Who cares if he kicked over the traces

As a youth? And when it came to faces,

Queen Victoria was no oil painting.

Is that the sound of royalists fainting?

Hold your horses! The Queen was an old podge,

You can’t deny it. She ate too much stodge

And had a gargantuan appetite.

I only want to set the record right,

Given the disgust she felt for her son.

Her scorn for Bertie was second to none.

Bulging eyes? He was not the only one.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE ALBERT MEMORIAL

The Albert Memorial in Hyde Park,

Newly restored and lit up in the dark,

Is a wonder that defies description.

Built entirely by public subscription,

Ordinary folk, I’m pleased to report,

Rose to the challenge. A popular sort,

Among the people, was the Prince. Anywhere

You care to look you will find an Albert Square,

An Albert Terrace. They are everywhere.

Over one hundred and twenty thousand pounds

The Memorial cost. The figure astounds.

It stands on the southern edge of the grounds

Of Kensington Gardens, west of the Park –

A fine revivalist Gothic landmark.

The edifice took ten years to complete.

Some one hundred and seventy-six feet

It measures in height, a single gold cross

At its apex. I’m almost at a loss

To know where to begin: the canopy,

Studded with figures from allegory,

The four arts (architecture, poetry,

Painting and sculpture) in fine mosaic;

Below its cornice (nothing prosaic),

The inscribed legend of dedication,

The heartfelt gratitude of the nation:

“From Queen Victoria and her People”.

Rising like a kind of ornate steeple,

Or Gothic ‘ciborium’, as it’s called,

It shelters the seated Albert, installed,

A pensive subject, on a golden throne.

The statue is crafted in bronze, not stone,

Affording a view of the Albert Hall.

The base of the massive Memorial

Is an elaborate sculptural frieze.

Here images of poets take their ease,

With architects and painters. Set above,

On each of the four corners, hand in glove –

For there is a unity of design

And purpose behind this amazing shrine –

Are Victorian figures depicting

The industrial arts, celebrating

The sciences of commerce, engineering,

Agriculture and manufacturing.

The further edges of the area

Show groups representing America

(Both North and South), Asia, Africa

And Europe – one corner per continent.

Featured in these groups are an elephant

(For Asia), a camel (Africa),

A bull (Europe) and (for America)

A bison – a tour of the Empire

Second to none, and designed to inspire.

Since the Monument’s restoration,

It stands as a credit to the nation

And is a permanent celebration

Of Albert’s talents, which were beyond belief.

His massive statue is covered in gold leaf:

It dazzles, it sparkles, it glints in the sun –

As a royal, the Prince was second to none.

Back to top / Buy the book

MRS ISABELLA BEATON

Before we go on, we should pause for breath,

Take stock and record another sad death.

The loss of some military hero?

A poet, composer or artist? No.

Yet another pesky politician?

A scientist or mathematician?

Make way for Mrs. Beeton, if you please.

Women of Great Britain! Down on your knees!

Her famous Book of Household Management

Was the housekeeping Bible, Heaven-sent.

Married to a publisher, Mrs. B

Fast became the leading authority

On household hints and home economy,

Amassing a “formidable body

“Of domestic doctrines” – one of the views

Voiced by The Illustrated London News.

Recipes were Mrs. Beeton’s main strength.

Magpie-like, she would go to any length

To collect suggestions from others.

An army of women, wives and mothers,

Sent in over 2,000 recipes.

She rarely tested them, but it was these,

Nonetheless, that Isabella published.

Her reputation has been rubbished

By modern critics. Not that I’m surprised.

Other works she routinely plagiarised,

Though few folk apparently seemed to care.

With true devotion, passion and flair,

She researched and produced her unique book.

In print today, it is well worth a look.

Running to eleven hundred pages,

It includes advice on servants’ wages,

How best to reply to invitations,

How to handle awkward situations –

Whether it was the ‘done thing’ to take your dog

On visits – even how to spit-roast a hog,

Or make ox-cheek soup. She made the odd mistake.

She once published a recipe for sponge cake,

Omitting (an error that no one should make)

The measure of flour required. Too bad!

Mrs. Beeton’s book was the best to be had.

Alongside the plethora of recipes

Was a separate chapter of remedies

For common ailments (what medicine? which pill?),

Even, I kid you not, how to make a will.

What comes as a surprise is that Mrs. B,

In spite of coming from a large family –

One of twenty-one children, yes, really –

Was lacking in personal experience

Of household management. Her sound common sense,

And her infallible feminine instinct,

Carried her through. First-year sales (what do you think?)

Topped 60,000. That was some achievement.

Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management

Quickly became the indispensable guide

For middle-class women, from the newest bride

To elderly matrons. The critics may sneer,

But hers was a truly amazing career.

‘Mrs. Beeton’ soon became a household name

In the hallowed Victorian ‘Hall of Fame’.

Her “no-nonsense asides” and her “brisk comments”

Were much praised. Never one to sit on the fence,

Her impact and influence, both, were immense.

The Book was a publishing sensation.

A “treasure”, indeed, it swept the nation,

A “valuable repertory of hints”

(Saturday Review). Never, before or since,

Had Britain seen its like. “Nothing omitted,”

Enthused The Morning Chronicle. “Explicit

“And intelligible,” raved the reviewer

For The Bradford Observer. Fresher, newer,

The Book was “almost of the first magnitude”.

‘Almost’? Well, I consider that rather rude.

Imagining Mrs. Beeton in the past,

I conjured up a grand old soul, built to last,

A solid, maternal sort. You’ll be aghast,

I’m sure, to learn that she died aged twenty-eight,

A fever in childbirth her terrible fate.

Poor woman. In 1865 she died –

A remarkable life, it can’t be denied.

Back to top / Buy the book

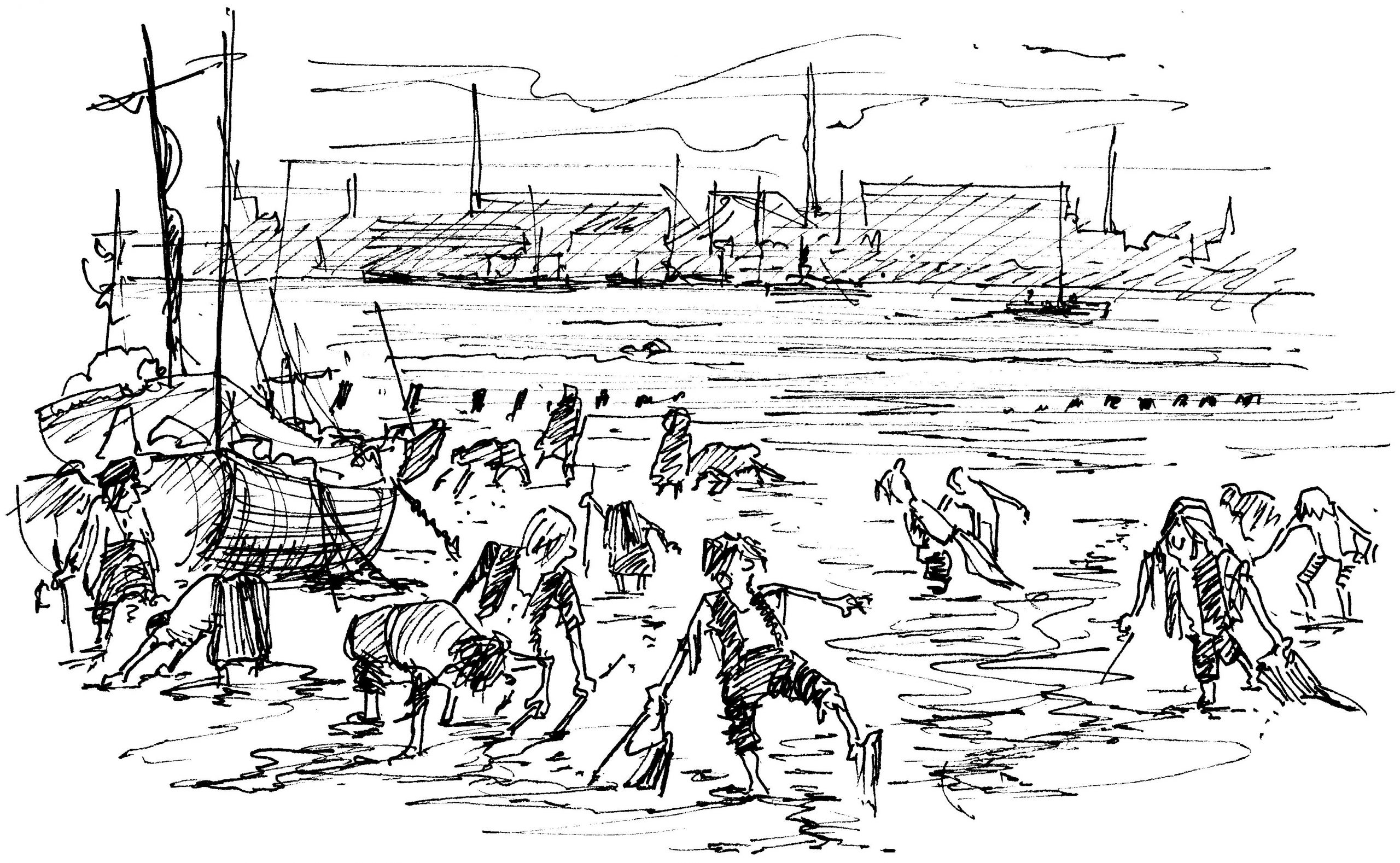

MUD-LARKS

Meet the mud-larks, usually children,

Small boys in the main, some as young as ten,

Though Mayhew encountered one who was six.

Garbed in filthy rags, a motley mix,

They waded through the mud up to their waists –

Believe me, the work was not to all tastes –

At low tide on the banks of the river.

Nails, copper, iron (any old sliver),

Coal, rope and bones (cheap fuel for the poor),

The mud-larks scavenged for these on the shore.

They collected their treasure of metals,

Flotsam and jetsam, in old tin kettles,

Even in the caps they took off their heads.

They slept in alleyways (having no beds),

The length of the river between Woolwich

And Vauxhall. They boasted barely a stitch –

Half-naked, exploited and underfed.

One sad specimen, whose father was dead,

Had no shoes. It was very cold, he said,

In winter to have to stand in the mud –

Imagine that, when the Thames was in flood –

But he did not mind it in the summer!

For this wee mud-lark was no newcomer:

Three years he’d been working. Now he was nine.

A penny a day? That suited him fine,

In the boy’s own humble opinion.

The case of another young minion

Caught Mayhew’s attention. A sharp nail

Punctured his foot, but the lad, without fail,

Returned to the river without delay.

He could hardly afford to miss a day,

For he gave his mother money for bread.

If he didn’t find anything, he said,

They lived as best they could. Asked about God,

He knew little. Why should a boy, unshod,

Unclothed, a scavenger for coal and wood,

Be concerned with such trifles? God was good,

He believed, but what use was He to him?

This one little mud-lark was far from dim.

Back to top / Buy the book

EMPRESS OF INDIA

Queen Victoria, in ’76,

Became Regina et Imperatrix –

Empress of India as well as Queen.

It’s fair to say that she was rather keen,

And this was Dizzy’s doing. As we’ve seen,

Her daughter Victoria, Crown Princess

Of Germany, would one day be Empress,

Once Kaiser Wilhelm, her father-in-law,

Popped his clogs. What a monumental bore,

Her Majesty felt, to take second place

To Vicky – nothing short of a disgrace.

By virtue of the Royal Titles Act,

The Queen gained what she hitherto had lacked,

The honour of an imperial crown!

The Commons sought to talk the measure down.

Gladstone played up, but Dizzy got his way.

Showman to the last, this was a display,

For sure, of vanity and bravado.

Great Britain, he wanted the world to know,

Was an Asiatic power, a force

To be respected. India, of course,

Was the Jewel in the Crown. Do or die,

The Queen was now ‘Victoria R. I.’

The title was far from pie in the sky.

The Empire grew, as the years rolled on,

Under Disraeli, even Gladstone

(Strange to say) and, more particularly,

In the ‘golden’ years of Lord Salisbury.

Great Britain’s imperial legacy

Caused many mixed feelings, as we shall see,

A source of conflict and controversy.

Speaking of new titles, in the same year

The Prime Minister’s health declined, I fear.

He left the Commons, as he felt he must,

Its late-night sittings and its cut-and-thrust,

For a seat in the Lords (as dry as dust).

‘Beaconsfield’, the title of his late wife

(Mary Anne) he now became.* The hard life

Of the Commons he gave up for the Lords,

The relative peace retirement affords.

Yet he stayed on as PM. “I am dead,”

Disraeli is alleged to have said,

“But in Elysian Fields.” The old man,

At seventy-one, was short of a plan,

But ironically there now began

The busiest season of his career.

Though Dizzy was praised to the skies, we hear,

His celebrity was wholly misplaced.

Indeed, he came close to being disgraced.

Back to top / Buy the book

THOMAS BARNADO

Another true Victorian hero

Was the wonderful Thomas Barnado.

China was where he was hoping to go,

On a Christian mission – but no.

Marking time before taking up his post,

He turned his thoughts to what troubled him most,

The poor and deprived of London’s East End.

He was appointed to superintend

The ‘Ragged School’, so-called, in Ernest Street,

Where dispossessed orphans could find their feet,

Whose families had died of cholera

(Some 3,000 victims). The sheer horror

Suffered by these abandoned waifs and strays,

Judged even by the standards of those days,

Cut Barnado to the quick. Lost, hungry

And ignored, this was real poverty.

How could they survive? He had cause to weep

When shown where children were forced to sleep:

On roofs, in gutters, in the cold night air.

Never one to hesitate or despair,

It was clear to Thomas what was lacking:

Homes! Families! Barnado got cracking.

To Victorians ‘poverty’ meant ‘shame’.

The homeless had only themselves to blame.

Well, not in young Thomas Barnado’s name.

The ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor –

What a distinction! Shocked to the core,

Barnado established homes by the score,

Here and overseas, for both girls and boys.

An autocrat, he made a lot of noise,

Fundraising, putting noses out of joint,

But he ploughed on. He did not disappoint.

By 1905, the year Thomas died,

He had opened ninety-six homes worldwide,

Caring for 8,500 (yes,

A massive number) children in distress.

Over 60,000 children, no less,

Had passed through his doors. Dr. Barnado

Was a soft touch. He would never say no.

Barnado’s never turn away a child.

Sadly, our hero was much reviled.

He had it coming! For he was ‘self-styled’ –

No ‘Doctor’ at all. Some said he kidnapped

The children. Thomas had his knuckles rapped,

Indeed he was sued, but to no avail.

Such a ludicrous charge was bound to fail.

One source claimed that he was Jack the Ripper!

Patently absurd. Ask any nipper.

Times change. But although the homes have long gone,

The work continues. The struggle goes on.

Barnado’s (this is quintessential)

Is devoted to the potential

Of every child, living anywhere,

Whatever their background. Support and care

Remain the watchwords of the charity.

Each child, whoever he or she may be,

And whatever his or her family,

Track record or place in society,

Has a fundamental right to be free:

Free from all prejudice, from poverty,

From the scourge of modern-day slavery

And all forms of domestic knavery,

Viz. physical and sexual abuse.

In the world today there is no excuse

For these wrongs, though sadly they still exist.

The new, modern Barnado’s will persist

In its fight against these injustices.

Its nine hundred and sixty services

Operate across most of the UK,

Addressing the key issues of the day:

Adoption (a more enlightened way

Than orphanages, I’m tempted to say);

Family forums, and fostering too;

Advice and comfort when somebody’s blue;

Extra support for children leaving care,

Which can lead to panic, stress and despair;

And, for youngsters caring for a loved-one,

Some acknowledgement of a job well done.

Back to top / Buy the book

ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON

An exact contemporary of Gladstone

Was the great poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson –

Both born in 1809. As we have seen,

One poem of comfort to the grieving Queen

Was Tennyson’s epic, In Memoriam.

Inspired by the death of Arthur Hallam,

At twenty-two, his closest and dearest friend,

The poem’s impact is hard to comprehend

In these more cavalier times of ours.

But the Queen would read the verses for hours,

Over and over, and welcomed Tennyson

To Osborne House. Strangely enough, at Eton,

Hallam and Gladstone had enjoyed a friendship

That bordered on mutual hero worship.

This made for an awkward relationship

Between the great poet and the Grand Old Man.

Just a tad jealous, so the rumour ran,

Was each of the other’s place in Hallam’s heart.

Tennyson distrusted Gladstone, for his part,

As a politician (he was a fan,

For instance of Gordon – he of the Sudan);

And Gladstone himself was not uncritical

Of some of Tennyson’s verses. Cynical,

However, Gladstone was not. In ’83,

Tennyson became a peer and it was he,

Gladstone, who proposed him. When Tennyson died,

In ’92, the old Queen was mortified,

But in a touching (and unusual) scene,

The “dangerous fanatic” approached the Queen

And offered her (as a loan, you understand)

Arthur Hallam’s letters, all in his own hand,

Written to William Gladstone in his youth.

It’s a colourful and fascinating truth,

An intriguing little fluke of history,

That Tennyson, Gladstone and the Queen, all three,

Were entranced by that bright, particular star,

Arthur Henry Hallam. Destined to go far,

He died in the prime of life, a tragedy

(To be mourned, like Albert) for her Majesty,

For the PM, indeed for everyone –

But most of all for his dear friend, Tennyson.

The poet today is not to all tastes.

For seventeen years the desolate wastes

Of the soul, the terrors of loss and grief,

The private crises of faith and belief,

He explored in In Memoriam – yes,

This long it took to explore his distress,

The great Victorian concerns, no less,

Of religion, immortality,

The relation of reality

To the unconscious, the place of art

In an everyday world. Where to start?

In Memoriam was a huge success.

It struck a chord in the consciousness

Of the age. But at 3,000 lines long,

It is quite a struggle. Don’t get me wrong,

As an epic it’s a fine achievement,

But today, suffering a bereavement,

The poem would offer little solace.

My advice would be to give it a miss.

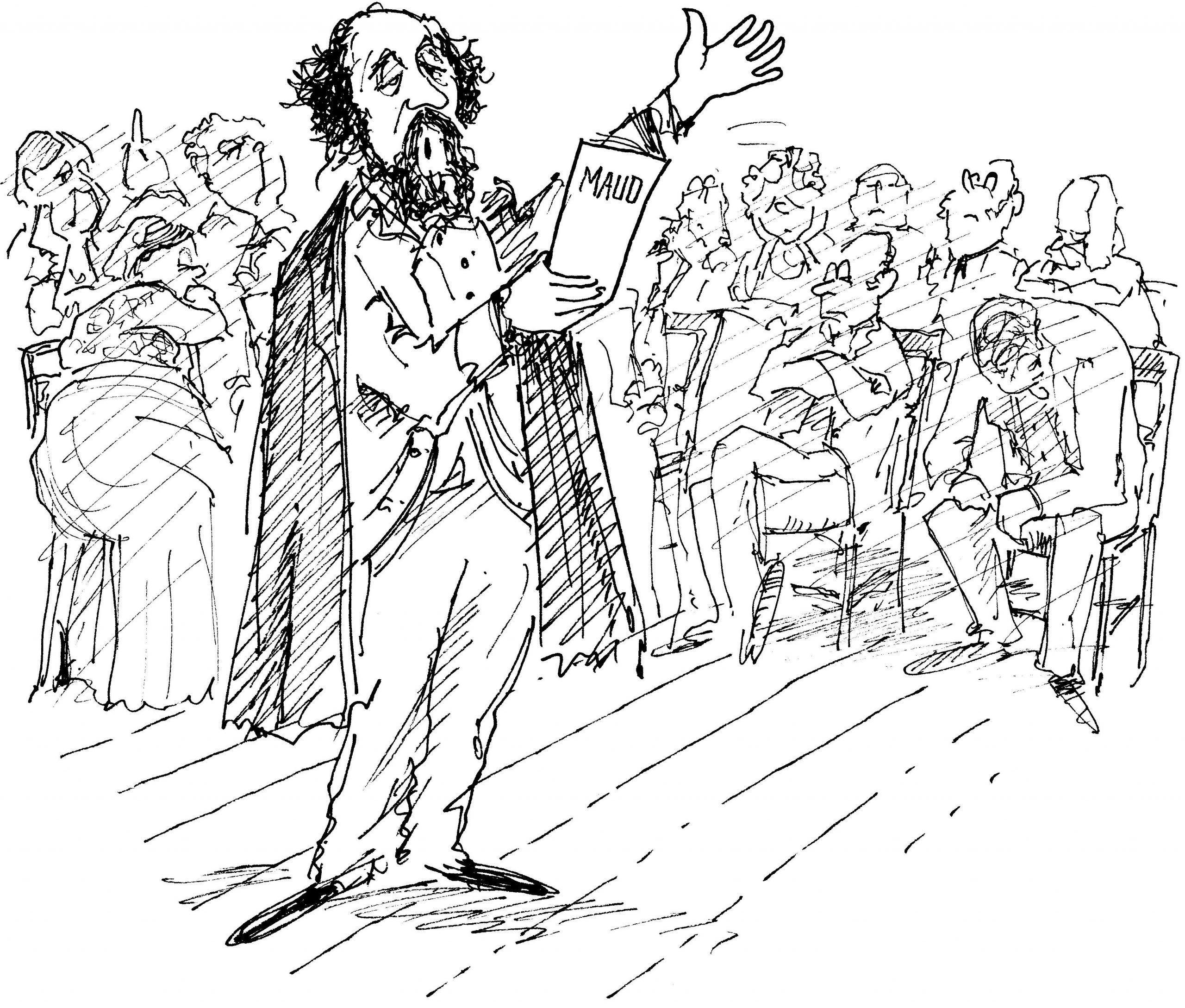

In his lifetime, Tennyson’s poem Maud

Was less popular. The poet’s reward

Was critical abuse. Alfred called it

(Modest he was not) his “little Hamlet”.

This was singularly appropriate,

For the narrator goes mad. His father,

Swindled by his business partner,

Has taken his own life. This sad young man,

Our hero, a humble artisan,

Falls for Maud, the partner’s daughter, rich,

Beautiful and chaste. There’s only one hitch:

She is socially far above him.

There is no chance Maud will ever love him.

A story of death, despair and torment,

For all its melodramatic content,

Maud is a triumph, a blistering read.

The famous Locksley Hall, most are agreed,

Crossing the Bar, The Lady of Shalott

And Ulysses are all well worth a shot,

Even, depending how much time you’ve got,

The Lotos-Eaters and Mariana.

But I urge you again, for sheer drama,

Take up Maud. Tennyson’s own favourite,

He’d read it aloud, although (wait for it)

The poem lasted over an hour!

His rendition was of such power

(In Tennyson’s view) that, as a refrain,

He’d perform the piece all over again.

Three straight sessions, we’re told, was the record

For the Poet Laureate’s reading of Maud.

All protestations were roundly ignored

That anyone (Heaven forfend) would be bored

Back to top / Buy the book

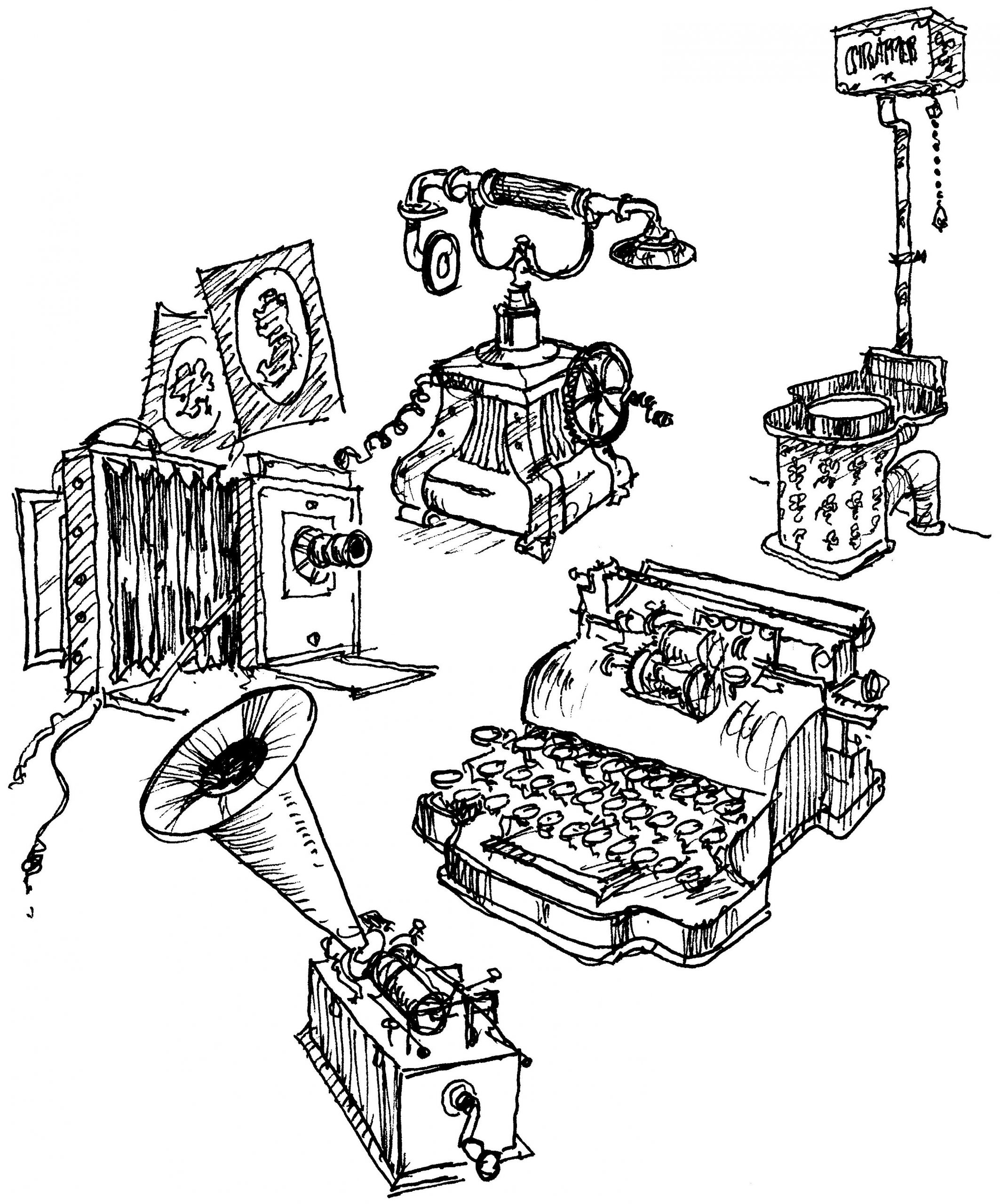

THE VICTORIAN AGE

The epitome of modernity –

That was the Victorian age. To us,

Looking back, our forebears seem tedious,

Stuffy and stern. That’s patently absurd.

‘Exciting’ would be a far fitter word,

‘Imaginative’ and ‘enterprising’.

The progress they made, far from surprising,

Was born of certainty and confidence.

Take on the world! It made absolute sense.

I shall make no great effort to defend

Their arrogance and pride, nor to pretend

That their guiding spirit of laissez-faire –

A kind of social ‘devil-may-care’ –

Inflicted neither injury nor pain.

But since ‘progress’ was their constant refrain,

We should pause, at least, to measure the gain.

At the start of Victoria’s long reign,

Very few people had been on a train.

Yet the railways transformed society.

The stage coach, the horse-drawn variety,

Trundled on (its decline was gradual),

But when it came to long-distance travel

The railway was king, with miles of new track

Laid year on year. There was no going back.

The sailing ship was a thing of the past,

For this was the age of steam. Built to last,

Steamships were ‘in’ and ploughed the seven seas.

The Navy, one of Great Britain’s glories,

And among her many success stories,

Embraced steam power and dispensed with sail.

Die-hards fought these advances tooth and nail,

But this was progress. New technology

Took the world by storm: from photography

To the telephone; from the phonograph

And the typewriter to the telegraph;

From the humble water closet (don’t laugh),

Patented by Thomas Crapper (so crude

To mock him, I have no wish to be rude),

To the awesome tunnels built underground

To ferry waste, whose value, pound for pound,

Was the greatest investment ever made

By the Victorians. Health, I’m afraid,

And basic standards of public hygiene,

Were sadly lacking – or rather had been,

Before the Victorians came along.

I make no claim that they did nothing wrong,

But their sewerage system, to this day,

Serves us well (despite some signs of decay).

There was also the underground railway

(Or ‘the tube’); there were bicycles, of course,

Cheaper (and cleaner by far) than the horse;

There was tinned food, refrigeration

And electric light. Transportation

Of convicts to overseas colonies –

One of the more gruesome realities

Of our justice system; the flogging

Of soldiers and sailors; the baiting

Of animals: these were things of the past.

Public executions, at long last,

Were brought to an end (though some were aghast).

It was free access to education

That produced a whole new generation

Of readers, leading to a huge boost in sales

Of newspapers. Where literacy prevails,

The common man will take an interest

In politics. That is all for the best.

Whether the Queen had much to do with this,

I have my doubts. “Where ignorance is bliss”

(The saying goes), “’tis folly to be wise.”

Victoria was taken by surprise

By many of these changes. She approved

Of army floggings and remained unmoved,

In general, by the plight of the poor.

She’d quickly have shown Gladstone the door,

Had she been able, and this I deplore.

The ‘Widow of Windsor’, all said and done,

Was rather a tartar, and not much fun.

Back to top / Buy the book

EDWARD THE SEVENTH

The new King set to work without delay.

At Buckingham Palace he cleared away

Much of his mother’s clutter. He removed,

Or burned, papers of which he disapproved,

Those of the Munshi in particular.

Bertie’s pursuits (‘extracurricular’,

To say the least) were far from ‘bespoke’.

The King was an easy-going bloke.

Windsor Castle, now thick with cigar smoke,

Was cleansed of all evidence of John Brown.

Statues of the wretched Scot were torn down

And smashed: King Edward, the iconoclast,

Rid of the Queen’s ‘highland servant’ at last.

Victoria’s wayward son and heir

Turned out to be a breath of fresh air.

‘Poor Bertie’, in fact (now here’s a thing),

By all accounts proved a popular King.

Vale Victoria! Let’s turn the page

And welcome in the Edwardian age.

Back to top / Buy the book